The Circus of Nero (also known as Circus of Caligula or Circus Gaius) was an ancient Roman arena that was located where St Peter’s Basilica now stands.

Circus of Nero location

The Circus was located in what is now the Vatican City, and St Peter’s Basilica now covers much of its footprint.

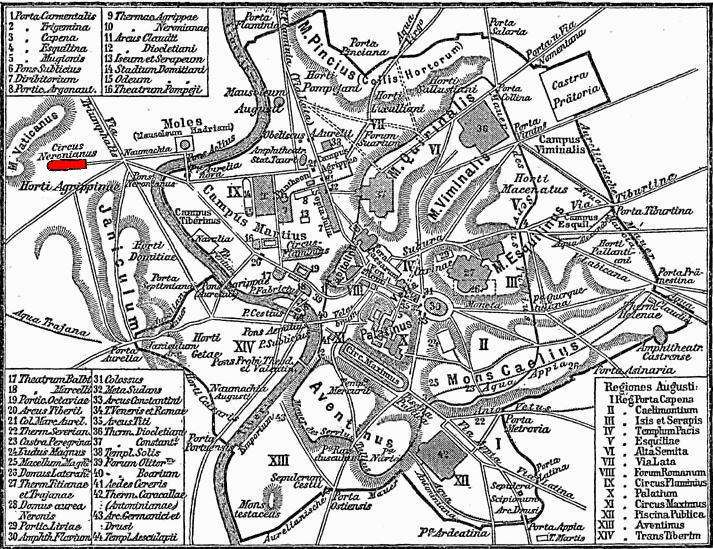

Maps of the ancient city will show that after crossing the Pons Aelius from the Campus Martius, head west along the Via Cornelia until you reach the Circus. The northern side of the Circus ran parallel to the Via Cornelia.

History of the Circus

Emperor Caligula began building the Circus during his short reign (AD 37-41), and his successor, Claudius, completed it.

The area of what is now the Vatican was reserved for wealthy people who wanted to build private residences and gardens away from the city itself. This led to the Circus beginning life as a private arena reserved for the emperor and his closest entourage.

However, when Nero became emperor, he opened the residences to the public. He had hoped that the public would cheer him on.

As noted by Tacitus in his book Annals, XIV, XIV, Nero trained in the Circus privately before opening the Circus up to the public:

“It was an old desire of his to drive a chariot and team of four and an equally repulsive ambition to sing to the lyre in the stage manner. “Racing with horses,” he used to observe, “was a royal accomplishment and had been practiced by the commanders of antiquity: the sport had been celebrated in the praises of poets and devoted to the worship of Heaven. As to song, it was sacred to Apollo, and it was in the garb appropriate to it that, both in Greek cities and in Roman temples, that great and prescient deity was seen standing.” He could no longer be checked when Seneca and Burrus decided to concede one of his points rather than allow him to carry both, and an enclosure was made in the Vatican Valley, where he could maneuver his horses without the spectacle being public. Before long, the Roman people received an in form and began to hymn his praises, as is the way of the crowd, hungry for amusements and delighted if the sovereign draws in the same direction. However, the publication of his shame brought with it not the satiety expected but a stimulus, and, in the belief that he was attenuating his disgrace by polluting others, he brought on the stage those scions of the great houses whom poverty had rendered venal. They have passed away, and I regard it as a debt due to their ancestors not to record them by name. For the disgrace, in part, is his who gave money for the reward of infamy and not for its prevention. Even well-known Roman knights he induced to promise their services in the arena by what might be called enormous bounties, were it not that gratuities from him who is able to command carry with them the compelling quality of necessity.”

It is also worth noting that in Roman times, competing in chariot races, gladiatorial contests, or performing on stage in a theater were considered lowly activities beneath the prestige of an emperor. This disdain is borne out by the words written by Tacitus.

The great fire of Rome in AD 64 cleared large swathes of land in central Rome, with many speculating that Nero was involved in starting the fires. Nero tried to deflect the blame away from himself, instead blaming the fire on Christians. As noted by Tacitus in Book XV, XLIV:

“But neither human help, nor imperial munificence, nor all the modes of placating Heaven, could stifle scandal or dispel the belief that the fire had taken place by order. Therefore, to scotch the rumor, Nero substituted as culprits and punished with the utmost refinements of cruelty, a class of men, loathed for their vices, whom the crowd styled Christians.”

This led to the first persecutions of Christians within the empire, and Nero was happy to the most of an advantageous situation, using his Circus to persecute followers of the new religious sect. As noted by Tacitus further in the same chapter of his book – XV, XLIV:

“First, then, the confessed members of the sect were arrested; next, on their disclosures, vast numbers were convicted, not so much on the count of arson as for hatred of the human race. And derision accompanied their end: they were covered with wild beasts’ skins and torn to death by dogs, or they were fastened on crosses and, when daylight failed, were burned to serve as lamps by night. Nero had offered his Gardens for the spectacle and gave an exhibition in his Circus, mixing with the crowd in the habit of a charioteer or mounted on his car.”

However, the crowd soon realized that the actions taken by the emperor were appalling, even by Roman standards. As noted by Tacitus again in XV, XLIV:

“Hence, in spite of a guilt which had earned the most exemplary punishment, there arose a sentiment of pity due to the impression that they were being sacrificed not for the welfare of the state but to the ferocity of a single man.”

It is suggested that crucifixions were carried out in the Circus, most likely in the middle section (where the chariots would have to travel around during the races). It is also said to be where St Peter and St Paul were martyred.

The Circus fell out of use during the second century AD as it went through various uses. The original St Peter’s Basilica was built on the Circus site during Constantine’s reign in the fourth century AD.

The Basilica incorporated some of the circus’ structure, marking a poignant moment in history where a place that was used to persecute Christians was destroyed and replaced by one of Christianity’s holiest sites. This is where St Peter is buried.

Much of the old Circus was destroyed in AD 1450 when the new St Peter’s Basilica was built. The only remnant of the ancient Circus is the Egyptian obelisk that stood in the center of it. Caligula brought this obelisk to Rome, and it is located in St Peter’s Square.

Sources:

Tacitus – Annals (Thayer) – https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Tacitus/Annals/14A*.html#ref23

Featured image – Public domain