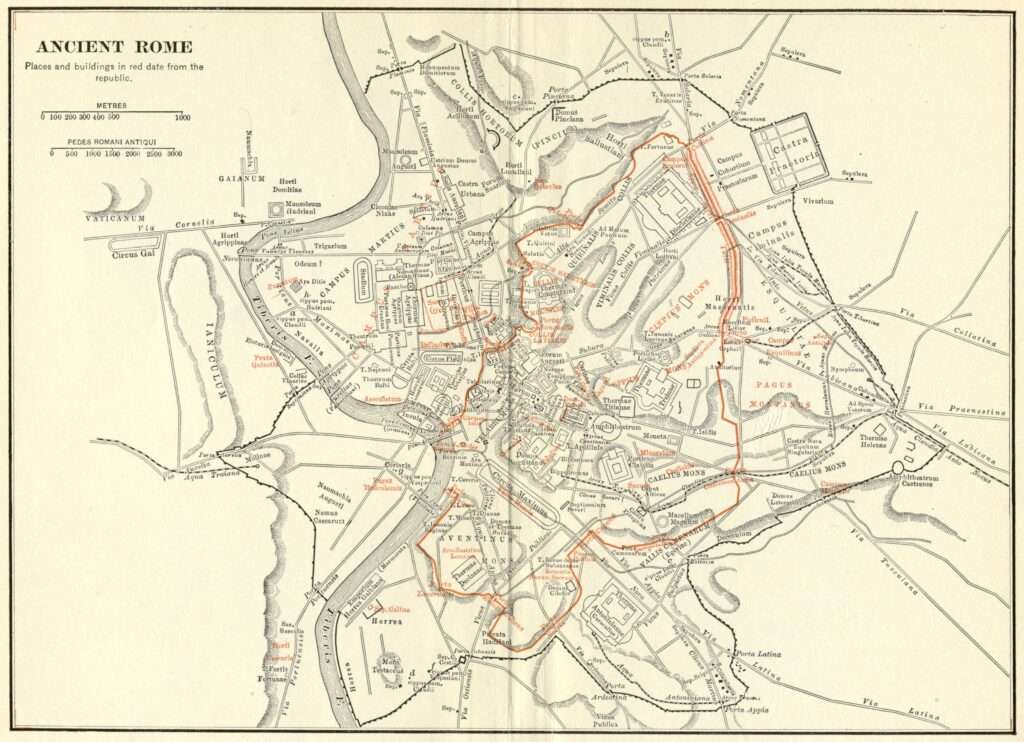

The Capitoline Hill (Mons Capitolinus) is located in the heart of the ancient civilization. It is renowned for being one of the most important locations in Roman history.

Location

Looking at a map of the ancient city, the Capitoline Hill was located on the western side of the ancient city, just inside the city’s first permanent defensive structure, the Servian Wall. It measures approximately 460m long and an average of 180m wide.

It was surrounded by buildings on at least three sides throughout its history.

To the west beyond the Servian Wall was the Campus Martius. In early Roman history, the Campus Martius was a plain that was relatively sparse in terms of buildings, as everything was conducted within the city walls. As time progressed and the city grew, many buildings occupied the Campus Martius.

Immediately west of the Capitoline Hill were buildings such as the Theater of Marcellus, the Porticus Octaviae, and the Circus Flaminius.

The Campus Martius was also located to the north of the Capitoline Hill but was also populated by buildings over the centuries.

Directly north, one would find the Saepta Julia (Porticus Saeptorum). Citizens and travelers would have seen the ancient Porta Fontinalis. This gate was the starting point of the Via Flaminia, which then linked up with the Porta Flaminia (the modern-day Porta del Popolo).

As time progressed, a section of the Servian Wall was removed in Imperial times so Emperor Trajan could construct his Forum. Part of Trajan’s Forum was north of Capitoline Hill – the Temple of Trajan, Trajan’s Column, and the twin libraries.

The heart of the city is northeast and east of the Capitoline Hill, with buildings packed in everywhere.

To the northeast, we have the rest of Trajan’s Forum, where you would have seen the Basilica Ulpia, the Forum Square itself, the bronze statue of Trajan, and Trajan’s Market.

East of the Capitoline Hill, one would find the Forum of Caesar, Forum of Augustus, Forum of Nerva, Curia Julia, Temple of Peace, and the Basilica Aemilia.

In the southeast, one would find the Velabrum, which was a valley in between the Capitoline and Palatine Hills, which itself was also located southeast of the Capitoline. This valley would lead from the banks of the Tiber right up to the center of the city, where all the forums were located.

South of the Capitoline Hill was more open as it was close to the Tiber, which often flooded. Directly south was the Circus Maximus, while the Aventine Hill was located slightly further south than that.

Southwest, one would find the Forum Boarium and the Pons Aemilius, which spanned the Tiber River. Citizens of the early Roman civilization would also have seen the Pons Sublicius, an ancient wooden bridge that crossed the Tiber and was said to be sacred. This bridge was the first bridge to span the Tiber. It was also the only bridge that early Rome had for centuries and could be pulled down and destroyed when needed in times of war.

Also located southwest were the Porta Carmentalis and the Porta Flumentana.

History

The Capitoline Hill (Mons Capitolinus) was occupied by the ancient Sabines (who maintained a citadel on the Hill), while the first Romans occupied the Palatine Hill. As noted by Livy in his work, The History of Rome, Book I, XXXIII.II:

“The Palatine had been settled by the earliest Romans, the Sabines had occupied the Capitoline hill with the Citadel on one side of the Palatine, and the Albans the Caelian hill, on the other, so the Aventine was assigned to the newcomers.”

The Capitoline Hill was originally called the Saturnian Hill before it was occupied by the Romans, as noted by Dionysius of Halicarnassus in his Roman Antiquities, Book II, I.IV in his description of the earliest settlements on the land that is now Rome:

“Not long afterwards, when Hercules came into Italy on his return home with his army from Erytheia, a certain part of his force, consisting of Greeks, remained behind to be settled near Pallantium, beside another of the hills that are now enclosed within the city. This was then called by the inhabitants Saturnian Hill, but is now called the Capitoline hill by the Romans.”

The Tarpeian Rock is located on the southwestern side of the hill. This is the location where Tarpeia is supposedly buried after she betrayed the Romans to the Sabines, who were trying to retake their citadel in Rome’s formative years.

King Tarquinius Superbus (the seventh and last King of Rome) also built the Temple of Jupiter near the Tarpeian Rock late in the sixth century BC. It was said to be almost as large as the Parthenon in Greece. Structures were deconsecrated and moved to make room for the vast new temple. Upon beginning construction, the Romans received divine intimation, to which they paid great heed.

As Livy notes in Book I, LV.I regarding the building of the temple and the omens and portends that the Romans received:

“After the acquisition of Gabii, Tarquin made peace with the Aequi and renewed the treaty with the Etruscans. Then, he turned his attention to the business of the city. The first thing was the temple of Jupiter on the Tarpeian Mount, which he was anxious to leave behind as a memorial of his reign and name; both the Tarquins were concerned in it; the father had vowed it, the son completed it. That the whole of the area which the temple of Jupiter was to occupy might be wholly devoted to that deity, he decided to deconsecrate the fanes and chapels, some of which had been originally vowed by King Tatius at the crisis of his battle with Romulus, and subsequently consecrated and inaugurated.

Tradition records that at the commencement of this work, the gods sent a divine intimation of the future vastness of the empire, for whilst the omens were favorable for the deconsecration of all the other shrines, they were unfavorable for that of the fane of Terminus. This was interpreted to mean that as the abode of Terminus was not moved and he alone of all the deities was not called forth from his consecrated borders, so all would be firm and immovable in the future empire. This augury of lasting dominion was followed by a prodigy, which portended the greatness of the empire. It is said that whilst they were digging the foundations of the temple, a human head came to light with the face perfect; this appearance unmistakably portended that the spot would be the stronghold of empire and the head of all the world. This was the interpretation given by the soothsayers in the city, as well as by those who had been called into council from Etruria.”

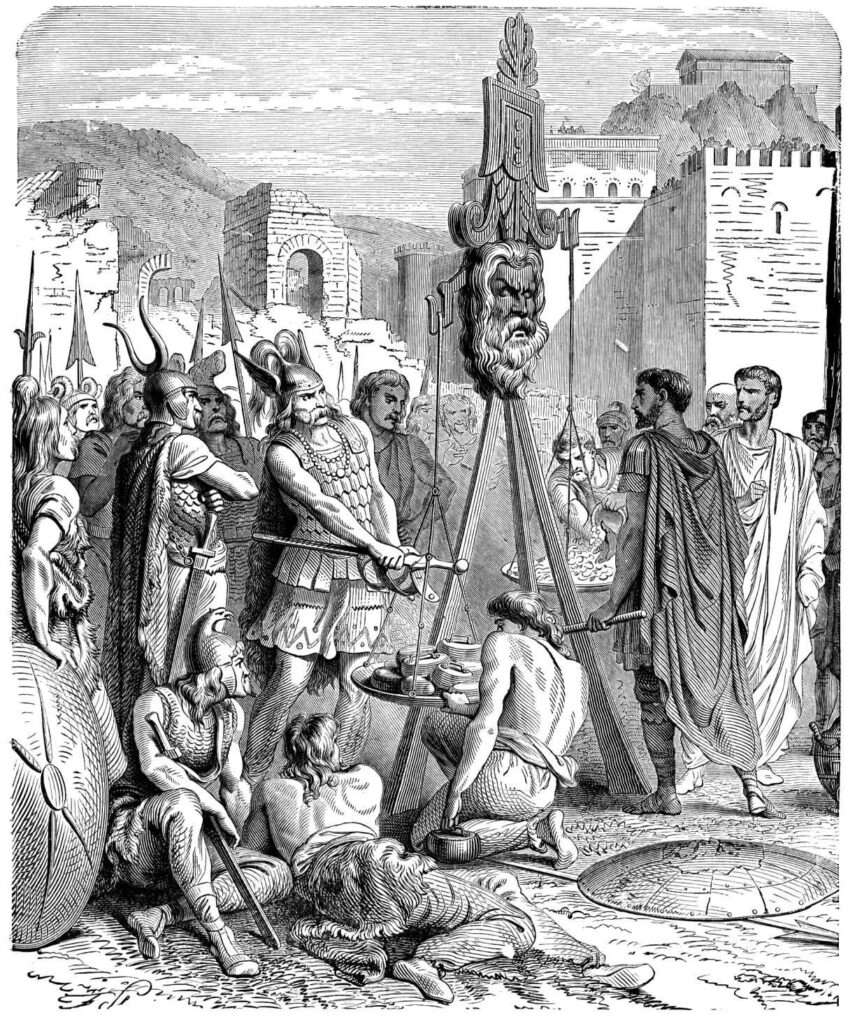

One of the most infamous events in Roman history involving the Capitoline Hill was the Sack of Rome by the Gauls early in the fourth century BC.

The Senones tribe, led by Brennus, defeated the Romans at the Battle of the Allia, several miles north of Rome. The defeat was so bad for the Romans that there were very few survivors of the battle. Some fled to nearby towns, while others returned to Rome.

by Paul Lehugeur (1886) – Public domain

The Gallic tribe made their way to Rome and, upon entering the undefended city, laid waste to it. As few fighting men were left, it was decided that parts of the population would be sent to the Capitoline Hill, which was well fortified, while many others were left to fend for themselves. These people were either killed by the invaders or fled to nearby towns.

Livy captures the tumultuous period in Book V, XXXIX.IX:

“Realizing the hopelessness of attempting any defense of the City with the small numbers that were left, they decided that the men of military age and the able-bodied amongst the senators should, with their wives and children, withdraw into the Citadel and the Capitol, and after getting in stores of arms and provisions, should from that fortified position defend their gods, themselves, and the great name of Rome. The Flamen and priestesses of Vesta were to carry the sacred things of the State far away from the bloodshed and the fire, and their sacred cult should not be abandoned as long as a single person survived to observe it. If only the Citadel and the Capitol, the abode of gods; if only the senate, the guiding mind of the national policy; if only the men of military age survived the impending ruin of the City, then the loss of the crowd of old men left behind in the City could be easily borne; in any case, they were certain to perish. To reconcile the aged plebeians to their fate, the men who had been consuls and enjoyed triumphs gave out that they would meet their fate side by side with them and not burden the scanty force of fighting men with bodies too weak to carry arms or defend their country.”

Dionysius of Halicarnassus confirmed this in Book XIII, VI.I:

“The gods gave ear to his prayers, and a little later, the city, with the exception of the Capitol, was captured by the Gauls. When the more prominent men had taken refuge on this hill and were being besieged by the Gauls, — the rest of the population had fled and dispersed themselves among the cities of Italy”.

This was one of the lowest points in Rome’s history and almost destroyed the ancient civilization. The Romans only survived by paying the invaders a large sum of gold to leave the city. The sacking of 390 BC was the last one for 800 years, when it was sacked by Alaric and the Goths in AD 410.

If we fast-forward to the first century AD, the Capitoline Hill is the scene of another battle – the civil war in AD 69, the year of the four emperors.

As war raged between Vitellius’ and Vespasian’s forces, Vitellius intended to cede Rome’s leadership to Vespasian through Vespasian’s brother, Sabinus.

However, upon hearing of the plan, some of Vitellius’ supporters were unhappy and decided to hunt down Sabinus. Sabinus fled to the Capitoline Hill and barricaded himself and some supporters (along with his nephew, the future emperor Domitian).

As Tacitus noted in his work, The Histories, Sabinus fled to the Capitol after a conflict with some Vitellian supporters. Book III, LXIX.I:

“The conflict was of trifling importance, for the encounter was unforeseen, but it was favorable to the Vitellian forces. In his uncertainty, Sabinus chose the easiest course under the circumstances and occupied the citadel on the Capitoline with a miscellaneous body of soldiers, and with some senators and knights”.

Sabinus’ supporters tried to keep the Vitellian supporters at bay by hurling rocks and other objects at the attackers from above as they made their way up the Hill.

Nearby houses were then set on fire, and the fire quickly spread around the Capitol, devastating many buildings and monuments. Among those buildings was the sacred temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus.

Tacitus laments the situation and writes of his horror and disgust about what happened on the Capitoline Hill and the destruction that took place. Book III, LXXII.I:

“This was the saddest and most shameful crime that the Roman State had ever suffered since its foundation. Rome had no foreign foe; the gods were ready to be propitious if our characters had allowed; and yet the home of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, founded after due auspices by our ancestors as a pledge of empire, which neither Porsenna, when the city gave itself up to him, nor the Gauls when they captured it, could violate — this was the shrine that the mad fury of emperors destroyed! The Capitol had indeed been burned before in civil war, but the crime was that of private individuals. Now it was openly besieged, openly burned — and what were the causes that led to arms? What was the price paid for this great disaster? This temple stood intact so long as we fought for our country.”

Some people were able to escape by various means. Domitian was able to conceal himself and escape. However, when the crowd caught up with Sabinus, they killed him despite the protestations of Vitellius.

The Capitoline Hill remained an important part of the ancient city throughout its history. However, the various temples located on it were largely abandoned and closed in AD 392 on the orders of the Christian Emperor Theodosius I, which was also a time of the pagan persecutions.

What is now on the Capitoline Hill?

The structures on the Capitoline Hill were replaced at various times over the centuries, as the ancient fell out of favor and were replaced by more modern buildings.

By СССР – CC BY-SA 2.5

The remnants of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, which had existed on the same site (in various forms) for over 2,000 years, was destroyed in the late sixteenth century. Palazzo Caffarelli was built in its place.

The Santa Maria in Aracoeli church was built in the twelfth century on the site of the ancient citadel.

The Piazza del Campidoglio, which houses the replica equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, was constructed in the sixteenth century. This piazza is also home to the Capitoline Museums – the Palazzo dei Conservatori and the Palazzo Nuovo. The Palazzo dei Conservatori was built in the Middle Ages, while the Palazzo Nuovo was built in the seventeenth century.

The Palazzo Senatorio stands atop the ancient Tabularium. It was constructed in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and parts of it were built using materials from the Tabularium.

There are also two colossal statues depicting the Dioscuri – Castor and Pollux. Between these two statues is the Cordonata, a sloped walkway/staircase (with few actual stairs) that allowed horses and other animals to move.

The reconstructed Colossus of Constantine is also now in place on the Capitoline Hill, with the original pieces still on display in the Capitoline Museums.

Sources:

The History of Rome – Livy (Perseus Digital Library)

Roman Antiquities – Dionysius of Halicarnassus (Thayer)

The Histories – Tacitus (Thayer)

Featured image – By Jean-Pierre Dalbéra CC BY 2.0