Ancient Rome was located on the banks of the Tiber River, and it needed bridges to enter and exit the city easily. Some have quite an illustrious history in their own right. Let’s take a look at the bridges of ancient Rome.

- Pons Milvius (Milvian Bridge)

- Pons Aelius (Ponte Sant’Angelo)

- Pons Neronianus

- Pons Agrippae

- Pons Aurelius/Antoninus

- Pons Fabricius

- Pons Cestius

- Pons Aemilius

- Pons Sublicius

- Pons Probi/Theodosii

Pons Milvius (Milvian Bridge)

Let’s start with one of the most famous bridges in ancient Rome – the Pons Milvius (Milvian Bridge).

The bridge was originally constructed in 206 BC using wood by the consul Gaius Claudius Nero. It was replaced in 109 BC by censor Marcus Aemilius Scaurus, who made it out of stone.

It is most famous as the site of the Battle of Milvian Bridge between Emperor Maxentius and Emperor Constantine. The battle took place on the northern side of the bridge.

As Maxentius’ army was poorly positioned to start the battle, things quickly turned ugly. The army was squeezed between Constantine’s army at the front and the Tiber River in the rear. Maxentius ordered the army to retreat back over the bridge (and a temporary wooden bridge alongside it) in the hopes of regrouping within Rome itself.

In the calamity that followed, many soldiers crossing the bridge fell into the Tiber, while the temporary wooden bridge collapsed. Maxentius also plunged into the river and drowned while trying to swim back to the southern bank of the Tiber.

As Zosimus noted in his book, New History, book II, XVI.IV:

“As long as the cavalry kept their ground, Maxentius retained some hopes, but when they gave way, he tied with the rest over the bridge into the city. The beams not being strong enough to bear so great a weight, they broke, and Maxentius, with the others, was carried with the stream down the river.”

The bridge has been repaired many times over the centuries but retains much of its Roman structure. It is still in use today.

By Livioandronico2013 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Pons Aelius/Ponte Sant’Angelo

Another rather famous Roman bridge. The Pons Aelius (Hadrian’s Bridge) was named after emperor Hadrian (his full name was Publius Aelius Hadrianus) and was built during his reign. It has been dated to AD 134.

It is famous for being the bridge one crossed to reach Hadrian’s Mausoleum, today’s Castel Sant’Angelo.

Legend has it that an angel appeared on the roof of the Castel, which marked the end of the plague. By extension, the bridge takes its name from the Castel (Ponte Sant’Angelo).

The bridge underwent extensive repairs over the centuries. It was also widened to allow more people to travel to the sacred areas of the Vatican, including St. Peter’s Basilica.

Some of the piers and arches that make up the bridge are original from the time of Hadrian.

By Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany – Pons Aelius (Bridge of Hadrian), Rome, CC BY-SA 2.0

Pons Neronianus

The origins of the Pons Neronianus are murky. We have yet to determine exactly when the bridge was constructed, with most historians agreeing that it was built during the reign of Caligula or Nero.

The bridge connected the western part of the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) to the Vatican Fields, which contained gardens. The Circus of Nero was also located nearby, giving citizens easy access to events at the circus.

By the late first century AD, triumphal marches began at the Pons Neronianus before continuing deep into the city center.

The bridge fell out of favor over the centuries as the Circus of Nero was destroyed and replaced with St. Peter’s Basilica. Most people used the nearby Pons Aelius as they crossed the bridge, passed by the Castel Sant’Angelo, and then onto the Basilica.

It was not listed in the fourth—and fifth-century AD document The Regionaries, an administrative text listing all of Rome’s important buildings. Other bridges are listed, but this one is not. This suggests it had been severely damaged or even destroyed by the fourth century AD.

The foundation piers lasted until the nineteenth century, when they were primarily destroyed to allow boats to navigate the Tiber easily. The very base of the piers can still be seen at low tide.

By ColdShine – Own photo., CC BY-SA 2.5

Pons Agrippae

The Pons Agrippae was built during Emperor Augustus’ reign and named after Agrippa, the emperor’s close friend and Roman general. Historians are unsure when the bridge was built, but it was likely constructed late in the first century BC.

The bridge was built so Agrippa could connect his villa on the western bank of the Tiber to the Campus Martius on the eastern side.

The bridge fell into disuse throughout the Middle Ages and was demolished by Pope Sixtus IV in the fifteenth century.

Nothing remains of the old Roman bridge.

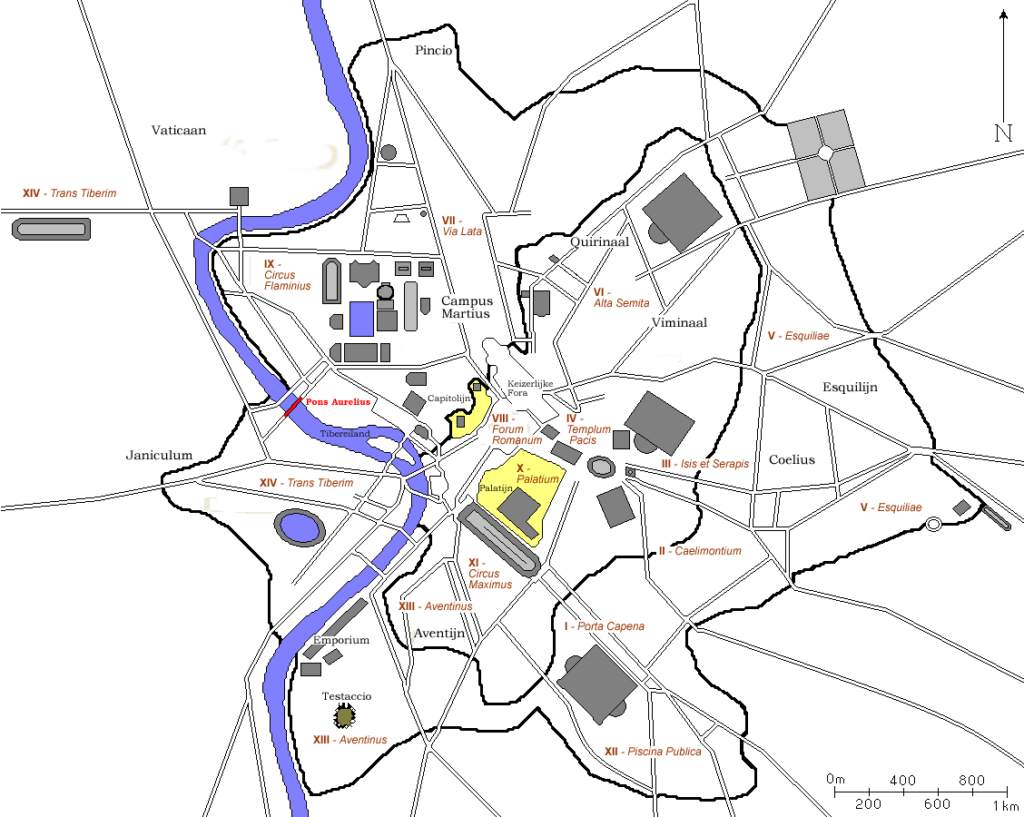

Pons Aurelius/Antoninus

It is unclear when the Pons Aurelius/Antoninus was constructed. Still, the name suggests that it was built during the second century AD during the Antonine dynasty (Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, etc.).

The Lombards largely destroyed the bridge in AD 772. Late in the fifteenth century, Pope Sixtus IV rebuilt it and renamed it Ponte Sisto, which is the name it currently goes by. Some of the material from the Pons Aurelius was used in the construction of the current bridge.

By fr:User:ColdEel & edited by nl:Gebruiker:Joris1919 – http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:AmphitheatreCastrense_planrome.png, CC BY-SA 4.0

Pons Fabricius

The oldest surviving Roman bridge still in its original form, the Pons Fabricius, was built in 62 BC. It was commissioned and built by Lucius Fabricius, who was in charge of roads and public works.

The bridge spans half of the Tiber River, reaching from the Campus Martius to the eastern bank of Tiber Island. It had replaced an earlier wooden bridge that had been destroyed. It was partially repaired in 23 BC after floods damaged it.

The bridge is still in use today.

Pons Cestius

The Pons Cestius was built sometime between the mid and late first century BC. The bridge spanned from Tiber Island’s western side to the Tiber River’s western bank.

The bridge was reconstructed in the second century AD, during the reign of Antoninus Pius.

The bridge was torn down and replaced by a better structure in the fourth century AD. This saw it re-dedicated as the Pons Gratiani, as the structure was built during the reigns of co-emperors Valentinian I and Valens, whose junior emperor was Gratian (Valentinian’s son).

It underwent several repairs and rebuilds before being demolished and rebuilt during the nineteenth century. Very little of the Roman bridge remains.

By Blackcat – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Pons Aemilius

The Pons Aemilius takes the title of the oldest stone bridge in the eternal city, having been built in the second century BC. This bridge replaced a wooden bridge constructed in the exact location.

The bridge underwent several changes in its early life. The stone bridge was built in the middle of the second century BC, and the arches were added almost a decade later. Augustus repaired the bridge, and Emperor Probus also repaired it in AD 280.

The Pons Aemilius was damaged several more times through the centuries due to floods.

The bridge is also famous for being the place where soldiers hurled emperor Elagabalus into the Tiber after killing him.

The book Historia Augusta – The Life of Elagabalus details the emperor’s death at the hands of Roman soldiers. Chapter XVII.I-II:

“Next, they fell upon Elagabalus himself and slew him in a latrine in which he had taken refuge. Then, his body was dragged through the streets, and the soldiers further insulted it by thrusting it into a sewer. But since the sewer chanced to be too small to admit the corpse, they attached a weight to it to keep it from floating and hurled it from the Aemilian Bridge into the Tiber in order that it might never be buried.”

Only a single arch from the bridge remains.

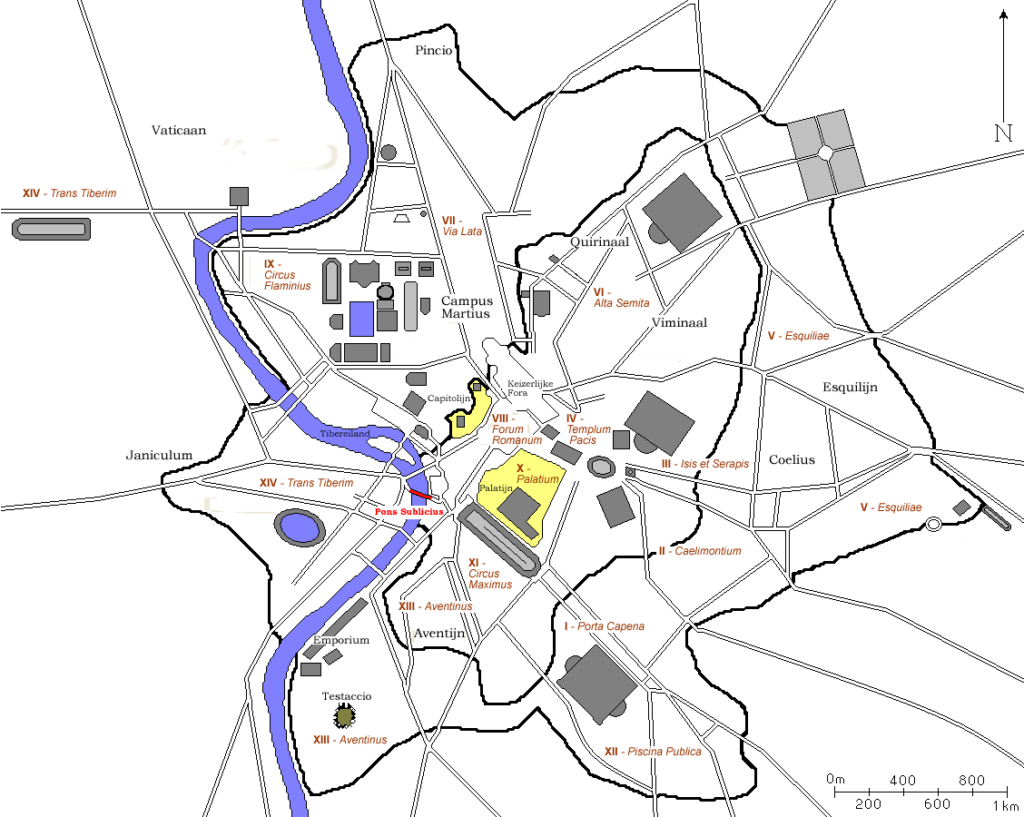

Pons Sublicius

The Pons Sublicius is the oldest known bridge in Rome and is also its most famous and illustrious. Built out of wood, the bridge was constructed during the reign of King Ancus Marcius in the Roman regal period. As no records of exact dates survive, the consensus is that the bridge was built around 642 BC.

The Roman historian Livy names the bridge in his book, The History of Rome, where he writes about the expansion of Roman territory under Ancus Marcius. Book 1, XXXIII.VI-VII:

“The Janiculum also was brought into the city boundaries, not because the space was wanted, but to prevent such a strong position from being occupied by an enemy. It was decided to connect this hill with the city, not only by carrying the City wall around it but also by a bridge, for the convenience of traffic. This was the first bridge thrown over the Tiber and was known as the Pons Sublicius.”

For centuries, it was the only bridge that crossed the Tiber River, with the earliest Romans little more than a tribe on the Palatine Hill. There was no need to expand across the Tiber in this civilization’s earliest phase. When expansion occurred, the need for a bridge materialized. The fact that it was made out of wood allowed the bridge to be dismantled quickly.

As Dionysius of Halicarnassus notes in his book, Roman Antiquities, book IX, LXVIII.II, the Romans could dismantle the bridge during times of conflict:

“There is no crossing it (the Tiber) on foot except by means of a bridge, and there was at that time only one bridge, constructed of timber, and this they removed in time of war.”

It had some religious significance, with the bridge coming under the direct control of the College of Pontiffs. Any damage caused to it was seen as a bad omen, and the bridge was repaired in a timely manner. This appears to be the case due to the legend of Horatius Cocles.

The legend has it that shortly after Tarquinius Superbus, the last King of Rome was deposed in 509 BC, the deposed King returned with an army to re-take Rome. In 508 BC, Tarquinius captured the Janiculum Hill (across the Tiber on the opposite side of Rome). With the bridge being the only way across the Tiber and into the city, Horatius Cocles stood up and protected his city by stalling the enemy on the far side of the bridge.

As detailed by Livy in The History of Rome, Book 2, X.I:

“On the appearance of the enemy the country people fled into the city as best they could. The weak places in the defences were occupied by military posts; elsewhere the walls and the Tiber were deemed sufficient protection. The enemy would have forced their way over the Sublician bridge had it not been for one man, Horatius Cocles. The good fortune of Rome provided him as her bulwark on that memorable day. He happened to be on guard at the bridge when he saw the Janiculum taken by a sudden assault and the enemy rushing down from it to the river whilst his own men, a panic-struck mob, were deserting their posts and throwing away their arms. He reproached them one after another for their cowardice, tried to stop them, appealed to them in heaven’s name to stand, declared that it was in vain for them to seek safety in flight whilst leaving the bridge open behind them, there would very soon be more of the enemy on the Palatine and the Capitol than there were on the Janiculum. So he shouted to them to break down the bridge by sword or fire or by whatever means they could; he would meet the enemies’ attack so far as one man could keep them at bay. He advanced to the head of the bridge. Amongst the fugitives, whose backs alone were visible to the enemy, he was conspicuous as he fronted them armed for a fight at close quarters. The enemy was astounded at his preternatural courage. Two men were kept by a sense of shame from deserting him —Sp. Lartius and T. Herminius —both of them men of high birth and renowned courage. With them, he sustained the first tempestuous shock and wild, confused onset for a brief interval. Then, while only a small portion of the bridge remained and those who were cutting it down called upon them to retire, he insisted upon these, too, retreating. Looking around with eyes dark with menace upon the Etruscan chiefs, he challenged them to single combat and reproached them all with being the slaves of tyrant kings and, whilst unmindful of their own liberty, coming to attack that of others. For some time, they hesitated, each looking round upon the others to begin. At length, shame roused them to action, and raising a shout, they hurled their javelins from all sides on their solitary foe. He caught them on his outstretched shield and, with unshaken resolution, kept his place on the bridge with firmly planted foot. They were just attempting to dislodge him by a charge when the crash of the broken bridge and the shout which the Romans raised at seeing the work completed stayed the attack by filling them with sudden panic. Then Cocles said, ‘Tiberinus, holy father, I pray thee to receive into thy propitious stream these arms and this thy warrior.’ So, fully armed, he leaped into the Tiber, and though many missiles fell over him, he swam across in safety to his friends: an act of daring more famous than credible with posterity. The State showed its gratitude for such courage; his statue was set up in the Comitium, and as much land given to him as he could drive the plough round in one day. Besides this public honor, the citizens individually showed their feeling; for, in spite of the great scarcity, each, in proportions to his means, sacrificed what he could from his own store as a gift to Cocles.”

It is unknown when the bridge was last rebuilt; however, we know it was still around in the fourth and fifth centuries AD as it was listed in the fourth and fifth-century document The Regionaries.

There are believed to be no remains of the Pons Sublicius, with evidence suggesting that the last remains were removed in the nineteenth century.

By fr:User:ColdEel & edited by nl:Gebruiker:Joris1919 – http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:AmphitheatreCastrense_planrome.png, CC BY-SA 4.0

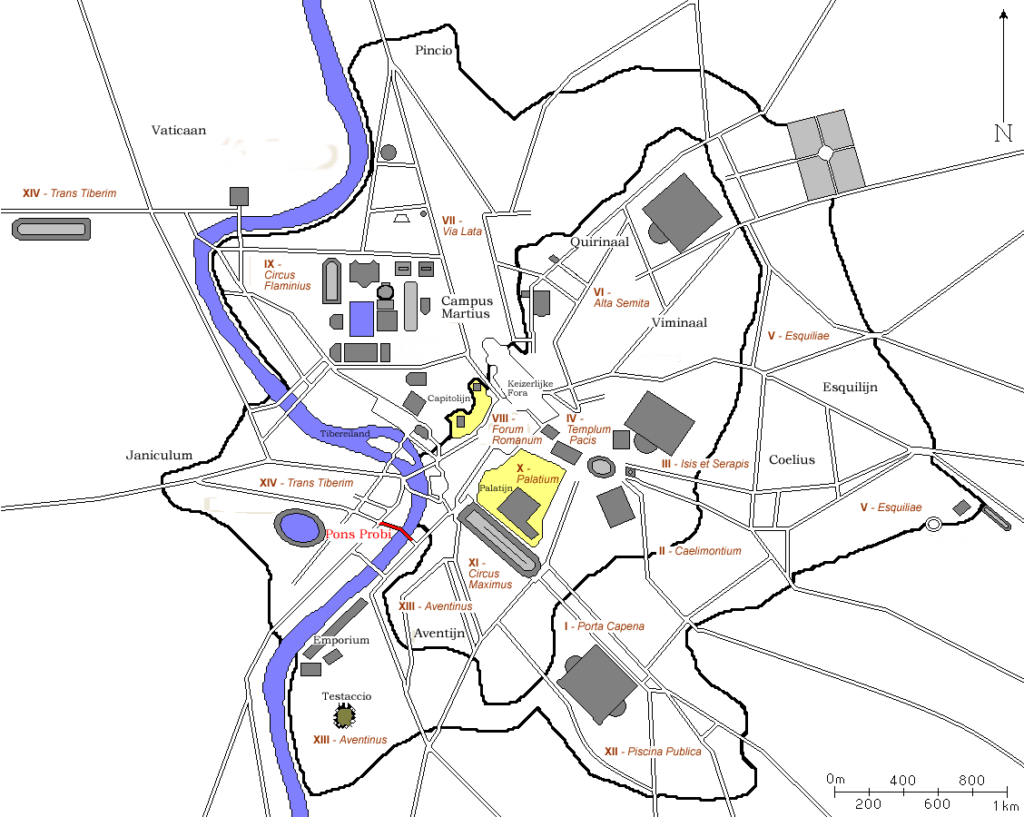

Pons Probi/Theodosii

There is little information regarding the Pons Probi. It is mentioned in the fourth and fifth century AD document, The Regionaries.

It was likely built during the reign of emperor Probus, who reigned between AD 276 and AD 282. It was the city’s southernmost bridge, crossing the Tiber from the base of Aventine Hill.

The bridge was severely damaged late in the fourth century and rebuilt under Emperor Theodosius. It was then known as Pons Theodosii.

The bridge underwent numerous repairs over its lifetime before being demolished by Pope Sixtus IV in 1484 (perhaps he could have learned a little restraint as it seems he was fond of destroying things!).

The last remnants of the bridge were removed in 1878.

By fr:User:ColdEel & edited by nl:Gebruiker:Joris1919 – http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:AmphitheatreCastrense_planrome.png, CC BY-SA 4.0

Sources:

Zosimus – New History (Livius.org) – https://www.livius.org/sources/content/zosimus/zosimus-new-history-2/zosimus-new-history-2.16/

The Regionaries (Thayer) – https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/L/Gazetteer/Places/Europe/Italy/Lazio/Roma/Rome/_Texts/Regionaries/appendices*.html#section_1C3.4

Historia Augusta – The Life of Elagabalus (Thayer) – https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Historia_Augusta/Elagabalus/1*.html#ref70

Livy – The History of Rome (Perseus Digital Library) – https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0026%3Abook%3D1%3Achapter%3D33

Dionysius of Halicarnassus – Roman Antiquities (Thayer) – https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Dionysius_of_Halicarnassus/9C*.html#68.2.3

Featured image – Public domain