The Aventine Hill was one of the Seven Hills of Rome. It is located in the southwest of Ancient Rome and was inhabited in early Roman history.

Location

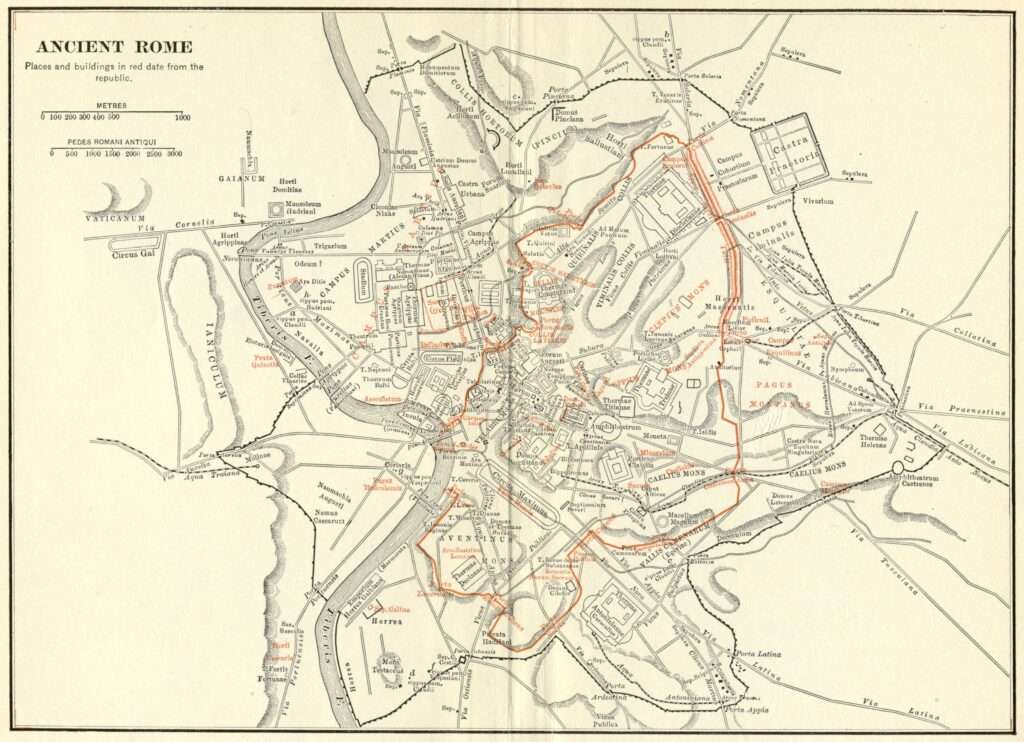

Looking at a map of Ancient Rome, one would see various structures and spaces, but it is located further from the center of Rome than any of the other Seven Hills. There are actually two hills, with a ‘depression’ in between. The smaller hill is usually regarded as part of the larger one, and thus, it is considered the Aventine Hill. They were sometimes called Aventinus Maior and Aventinus Minor in cases where a distinction needed to be made.

If we looked northeast of the hill, we would spot the nearby Circus Maximus. On the opposite side of the Circus, we would see the Palatine Hill, with the Imperial Palaces in plain sight.

Turning north, we find the Temple of Ceres (Templum Cereris) and the Great Altar of Hercules (Herculis Invicta Ara Maxima). The Forum Boarium was located a bit further north. This was the cattle market for the ancient city.

Finally, one of the 10 bridges of Ancient Rome was said to be located near the Forum Boarium—the Pons Sublicius. This ancient wooden bridge was the first to cross the Tiber and could be pulled down during war.

The northwest and west were dominated by the Tiber River, which the Aventine Hill butted up against. The Pons Probi (later rebuilt and called the Pons Theodosii) was also located in this area.

Also located near the north or northwest side (the exact whereabouts are still disputed) of the Aventine Hill is one of the 51 Gates of Ancient Rome, Porta Trigemina. This gate was most likely located along the strip of land between the Aventine Hill and the Tiber River and was part of the Servian Wall.

The west and southwest of the Aventine Hill was dominated by warehouses as it became the main industrial hub of the ancient city. This is because much of the goods that came by ship were offloaded at the port city of Ostia and then transported to Rome by road. They were transported along the Via Ostiensis and then brought to the warehouses for storage.

It is here that we find the Monte Testaccio (Mons Testaceus), a ‘hill’ made out of broken amphorae and other Roman pottery. The amphorae were used to carry olive oil and were believed to be unusable after their first use. The amphorae were then broken up and placed in this area, which eventually became covered in grass and shrubs.

To the south of the hill is the previously mentioned Via Ostiensis. When the Aurelian Wall was built, the Via Ostiensis passed through the Porta Ostiensis (Porta San Paolo). Slightly to the west of the Porta Ostiensis, there is the Pyramid of Cestius, which was a mausoleum. It was later incorporated into the Aurelian Wall. To the west of that, there was another gate of unknown name, but it was given the name Porta Ostiensis (west) in more modern times. This was a gate mainly used for the goods that arrived from Ostia.

Looking southeast, we would see the aqueduct, Aqua Antoniniana, and the Porta Ardeatina, with the Porta Appia and the Porta Latina being further away. Closer to the hill, we would spot the Thermae Antoninianae (Caracallae), also known as the Baths of Caracalla.

To the east of the hill, we would see the Caelian Hill in the distance, the Porta Capena, and the Septizonium.

Plenty of structures existed on the hill itself, which was enclosed by the Servian Wall in both parts.

Aside from the earlier-mentioned Porta Trigemina, the hill had three other gates that were part of the Servian Wall defensive fortifications. The Porta Lavernalis was located on the southwestern side of the larger portion of the hill (Aventinus Maior), the Porta Raudusculana was located in the “depression” that split both sections of the hill, while the Porta Naevia was situated on the southeastern slope of the smaller section of the Aventine (Aventinus Minor).

Rome’s oldest aqueduct, the Aqua Appia, crossed the Aventine Hill after cutting across the Caelian Hill and ending at the Forum Boarium.

The largest structure on the hill was the Baths of Decius (Thermae Decianae), built in the mid-third century AD and named after the Emperor of the same name.

There were also a few temples located on the hill—the Temple of Luna (Aedes Lunae), Temple of Diana (Aedes Dianae), Temple of Minerva (Aedes Minervae), Temple of Bona Dea (Aedes Bonae Deae Subsaxanae), and Temple of Juno Regina (Aedes Iuno Regina).

There were also a few notable residences on the hill—the Privata Hadriani (which was Hadrian’s residence before he was adopted by Trajan), Domus Cilonis, and the Domus of Surae, which was located near the Thermae Suranae (a bath complex).

History

The history of the Aventine Hill goes right back to the foundation story of the city itself.

The foundation story of Romulus and Remus states that the twin brothers were consulting the augurs when deciding who would lead this new civilization.

The story has both brothers standing on two hills in the area, waiting for signs from the gods as to who was supposed to lead this fledgling society. Romulus was stationed on the Palatine Hill, and Remus was stationed on the Aventine Hill.

By Giuseppe Vasi (Public domain)

As Livy noted in his work, The History of Rome, the difficulty in deciding who would lead the new society was based on the fact that since they were twins, there was no explicit claim to leadership in terms of seniority as they were twins. This is when the augurs were consulted. Book I, VI.IV:

“As they were twins and no claim to precedence could be based on seniority, they decided to consult the tutelary deities of the place by means of augury as to who was to give his name to the new city and who was to rule it after it had been founded. Romulus accordingly selected the Palatine as his station for observation, Remus the Aventine.”

Livy then explains how the leadership was decided and two slightly different versions of the aftermath, both resulting in bloodshed. Book I, VII.I:

“Remus is said to have been the first to receive an omen: six vultures appeared to him. The augury had just been announced to Romulus when double the number appeared to him. Each was saluted as king by his own party. The one side based their claim on the priority of the appearance, the other on the number of the birds. Then followed an angry altercation; heated passions led to bloodshed; in the tumult, Remus was killed. The more common report is that Remus contemptuously jumped over the newly raised walls and was forthwith killed by the enraged Romulus, who exclaimed, ‘So shall it be henceforth with everyone who leaps over my walls.’ Romulus thus became sole ruler, and the city was called after him, its founder.”

In his work, The Parallel Lives – the Life of Romulus, Plutarch confirms the events as outlined by Livy. Chapters IX.IV & X.I:

“But when they set out to establish their city, a dispute at once arose concerning the site. Romulus, accordingly, built Roma Quadrata (which means square) and wished to have a city on that site, but Remus laid out a strong precinct on the Aventine hill, which was named after him Remonium, but now is called Rignarium. Agreeing to settle their quarrel by the flight of birds of omen and taking their seats on the ground apart from one another, six vultures, they say, were seen by Remus and twice that number by Romulus. Some, however, say that whereas Remus truly saw his six, Romulus lied about his twelve, but when Remus came to him, then he did see the twelve. Hence, it is that at the present time also, the Romans chiefly regard vultures when they take auguries from the flight of birds.

When Remus knew of the deceit, he was enraged, and as Romulus was digging a trench where his city’s wall was to run, he ridiculed some parts of the work and obstructed others. At last, when he leaped across it, he was smitten (by Romulus himself, as some say; according to others, by Celer, one of his companions) and fell dead there. Faustulus also fell in the battle, as well as Pleistinus, who was a brother of Faustulus, and assisted him in rearing Romulus and Remus.”

According to Marcus Terentius Varro, the origin of the name is by no means certain, with a few theories given. He outlines these in his writings, On the Latin Language, Ch. V, XLIII:

“The name of the Aventine is referred to several origins. Naevius says that it is from the aves’ birds’ because the birds went thither from the Tiber. Others say that it is from King Aventinus the Alban because he is buried there. Others that it is the Adventine Hill, from the adventus ‘coming’ of people, because there a temple of Diana was established in which all the Latins had rights in common. I am decidedly of the opinion that it is from advectus’ transport by water’; for of old, the hill was cut off from everything else by swampy pools and streams.”

There is disagreement about the etymology of the name, with fourth and fifth-century AD writer Maurus Servius Honoratus (Servius the Grammarian) writing of his belief that the hill was named after birds or an Italic King (‘King of the Aborigines’ – the oldest known inhabitants of the land) also named Aventinus and that the Aventinus that Varro mentions gets his name from the hill, rather than the hill being named after him. In his works, Commentary on the Aeneid of Virgil, Book VII, VII.DCLVII:

“The beautiful Aventine Aventine is a mountain of the city of Rome, which is evidently named after the birds that sat there when they came up from the Tiber, as we read in the eighth, “the house of the wild birds convenient for their nests. “a certain king of the Aborigines, named Aventinus, was also killed and buried there, as was also Aventinus, king of the Albans, who was succeeded by Procas. Varro, however, says that among the race of the Roman people, the Sabines, having been received by Romulus, received that mountain, which they called the Aventine, from the Aventus, a river of their province. It is therefore evident that these various opinions were afterwards followed, for from the beginning, Aventinus was called by the birds or by the king of the Aborigines, whence it is evident that this son of Hercules received the name from the mountain and did not give it to him. He said, “Absolutely, the sign of the father.”

The fledgling kingdom’s borders expanded over time, with neighboring tribes absorbed into Rome’s dominion. As Rome expanded its borders and conquered other peoples, many of the vanquished were sent to Rome and integrated into the city, with the goal of growing the tiny civilization.

By Fiat 500e – CC BY-SA 4.0

In Livy’s book, The History of Rome, he outlines that Rome’s fourth king, Ancus Marcius, expanded his domain by conquering nearby Latin cities. The conquered were sent back to Rome and occupied the Aventine Hill. In Book I, XXXIII.I he writes:

“Ancus delegated the care of the sacrifices to the flamens and other priests and, having enlisted a new army, proceeded to Politorium, one of the Latin cities. He took this place by storm and, adopting the plan of former kings, who had enlarged the state by making her enemies citizens, transferred the whole population to Rome. The Palatine was the quarter of the original Romans; on the one hand were the Sabines, who had the Capitol and the Citadel; on the other lay the Caelian, occupied by the Albans. The Aventine was therefore assigned to the newcomers, and thither too were sent shortly afterwards the citizens recruited from the captured towns of Tellenae and Ficana.”

Dionysius of Halicarnassus goes further and writes in his work, Roman Antiquities, that King Ancus Marcius included the Aventine Hill within the city’s walls. Book III, XLIII.I:

“In the first place, he made no small addition to the city by enclosing the hill called the Aventine within its walls. This is a hill of moderate height and about eighteen stades in circumference, which was then covered with trees of every kind, particularly with many beautiful laurels, so that one place on the hill is called Lauretum or “Laurel Grove” by the Romans; but the whole is now covered with buildings, including, among many others, the temple of Diana. The Aventine is separated from another of the hills that are included within the city of Rome, called the Palatine Hill (round which was built the first city to be established), by a deep and narrow ravine, but in after times the whole hollow between the two hills was filled up. Marcius, observing that this hill would serve as a stronghold against the city for any army that approached, encompassed it with a wall and ditch and settled here the populations that he had transferred from Tellenae and Politorium and the other cities he had taken.”

One of the more interesting events regarding the Aventine Hill occurred during the Consulship of Marcus Valerius and Spurius Virginius. Thanks to records, we know that this event occurred between 456 and 455 BC.

Tensions between the plebeians and patricians existed for quite some time, in what became known as the First Aventine Secession (also the First secessio plebis), a civil conflict that lasted a few years. It came to a head during the Consulship of Marcus Valerius and Spurius Virginius. The tribunes and consuls were also in conflict, with the tribunes representing the plebeians.

The tribunes had proposed that the Aventine Hill should be declared a public area and used for public housing for the city’s poor. At the time, tribunes could not convene a hearing of the senate. This could only be done by consuls. The tribunes had voiced their wishes for a law to be passed stating this. Still, the consuls regularly delayed the presentation of the law and subsequent vote to the senate.

This enraged the tribunes, headed by a man named Icilius, who took it upon themselves to escalate the situation by capturing a representative of the consuls (known as a lictor). They then threatened to throw this person off the Tarpeian Rock but were persuaded by some old senators not to go through with it, citing the optics of such a measure and the escalation that would ensue.

This event was covered in great detail by Dionysius of Halicarnassus in his book Roman Antiquities, Book X, XXXI:

“The tribunes of the year in question were the first who undertook to convene the senate, the experiment being made by Icilius, the head of their college, a man of action and, for a Roman, not lacking in eloquence. For he too was at that time proposing a new measure, asking that the region called the Aventine be divided among the plebeians for the building of houses. This is a hill of moderate height, not less than twelve stades in circuit, and is included within the city; not all of it was then inhabited, but it was public land and thickly wooded. In order to get this measure introduced, the tribune went to the consuls of the year and to the senate, asking them to pass the preliminary vote for the law embodying the measure and to submit it to the populace. But when the consuls kept putting it off and protracting the time, he sent his attendant to them with orders that they should follow him to the office of the tribunes and call together the senate. And when one of the lictors at the orders of the consuls drove away the attendant, Icilius and his colleagues, in their resentment, seized the lictor and led him away with the intention of hurling him down from the rock……. but released the man at the intercession of the oldest senators; for they were not only concerned about the odium that would attend such a procedure, if they should be the first to punish a man by death for obeying an order of the magistrates but also feared that with this provocation the patricians might be driven to take desperate measures.”

The consuls eventually convened a session of the senate, where many were outraged at this event and hurled accusations at the tribunes. Icilius took to the floor of the senate and explained why these actions were taken. He also introduced the proposal for the Aventine Hill.

This law would allow private citizens on the hill to retain their land if they acquired it legally, and land gained fraudulently would be turned back over to the state. The law was voted on, and few objected to it. The Lex Icilia (named after Icilius) passed and was ratified after the various religious rites were carried out. The plebeians now had land to call their own.

Many temples (such as those mentioned previously were built on the hill during the Republican era.

The area began to change during the Imperial period as it became more aristocratic, with the wealthy and powerful alike moving there. Emperors Trajan and Hadrian resided there before becoming Emperor, while Emperor Vitellius also lived there. The Baths of Decius were built there, signifying its importance to the Imperial city.

What is now on the Aventine Hill?

Plenty of notable structures and sites are located within the Aventine Hill area, with churches featuring most prominently.

The Basilica di Santa Sabina all’Aventino is one of Rome’s oldest surviving churches. It was completed in AD 432 atop an old Roman house.

Built between the third and fourth centuries AD, the Santi Bonifacio ed Alessio is a basilica that underwent many restorations and changes over the centuries. Most notably, it was restored by Pope Honorius III in the early thirteenth century.

The Santa Prisca church was first built in the fourth or fifth century AD. It was built over the site of a Mithraeum, which itself sits atop a Roman house that belonged to Emperor Trajan before he became Emperor. The church was greatly damaged during the Norman Sack of Rome in 1084. The current iteration of the church is vastly different from the original, with a few columns being the only parts left of the ancient church.

The Santa Balbina church was built in the fourth century AD. It is located on the site of the old Domus Cilonis, which was previously mentioned in this article. In fact, the site was renovated rather than built over.

In addition to churches, there are numerous piazzas on the hill, while the Rome Rose Garden is a short distance from the Circus Maximus.

Sources:

The History of Rome – Livy (Perseus Digital Library)

The Parallel Lives – Plutarch (Thayer)

On the Latin Language – Varro (W. Heinemann)

Commentary on the Aeneid of Virgil – Maurus Servius Honoratus (Perseus Digital Library)

Roman Antiquities – Dionysius of Halicarnassus (Thayer)