Continuing with our series of Roman ruins, we take a look outside Italy. We’re off to the lands of Britannia, a once-fabled land on the edge of the ancient world, filled with mystics, druids, and savage warriors—a real mysterious ancient civilization to the Romans. Let’s look at some of the Roman ruins in England.

Hadrian’s Wall

Perhaps one of the most famous Roman ruins from antiquity is Hadrian’s Wall. As made evident by the name, the Wall was built during the reign of Emperor Hadrian. Construction began in AD 122 and took approximately six years to complete.

The Wall was approximately 73 miles (117 kilometers) long, running from modern-day Wallsend (hence the name) in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west. The Wall had strongholds spaced at least a mile apart, where detachments from the legions would be based.

The Wall was built by the legions stationed there at the time, as well as some soldiers from the Roman navy. The Wall varied in places, depending on the terrain.

The Wall was built as a defensive structure, stopping the constant raids and fighting between the Romans and the Picts of modern-day Scotland. Hadrian wanted to stabilize and consolidate the empire after decades of rapid expansion. He saw this as a way to “pause” and to continue developing, reforming, and improving the Roman provinces in Britannia. As mentioned in the book Historia Augusta – The Life of Hadrian, Book I, XI:

‘And so, having reformed the army quite in the manner of a monarch, he set out for Britain, and there he corrected many abuses and was the first to construct a wall, eighty miles in length, which was to separate the barbarians from the Romans.’

A later wall (the Antonine Wall) was built under Emperor Antoninus Pius about 100 miles (160 kilometers) north of Hadrian’s Wall but was abandoned less than ten years after completion, with the legions unable to pacify the area. The legions returned to Hadrian’s Wall, where border protection was more manageable.

Vindolanda

Vindolanda was a Roman military fort that lay just south of Hadrian’s Wall and pre-dated the Wall itself. Numerous forts have been built on the site at Vindolanda, first made out of wood and earth before the stone fort was constructed. The first fort at Vindolanda dates from approximately AD 85.

The fort and the adjoining village remained in regular use until AD 285, when the area was largely abandoned. The village resulted from the strong military presence along Hadrian’s Wall and the fort itself.

The fort was reoccupied in the fourth century AD, with repairs done around AD 370. It was again abandoned sometime in the late fourth century or early fifth century AD when the Romans retreated from Britannia as the empire began its decline.

Many excavations have been undertaken at the fort’s site, with archeologists finding all sorts of items related to military and civilian life at the fort and its surroundings. Among the finds were ink tablets, combs, arrowheads, swords, and even boxing gloves.

Due to the volume of finds, a museum (Chesterholm Museum) was constructed nearby. It showcases the various finds and gives visitors a chance to learn about life at the fort and Roman Britain in general.

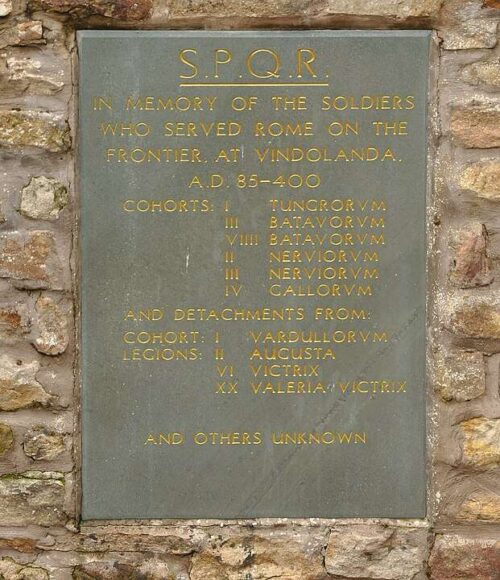

One of the great modern additions that have been made to the site is a memorial dedicated to the soldiers who were stationed at Vindolanda over the years.

Lindum Colonia (Lincoln)

Lindum Colonia (modern-day Lincoln) started life as a Roman fortress, housing troops during Roman expansion into Britannia. It was likely founded during the reign of Emperor Nero (AD 58-68) and originally garrisoned the fabled Legio IX Hispana before it moved on further north to build a fortress at Eboracum (York) in the AD 70s.

It was then converted to a colonia (Roman settlement) late in the first century AD; as more Romans moved to the area, the empire continued its “Romanization” of the region. Many retired legionaries also moved to the area. It was also an important center for pottery production, a product desperately needed for a burgeoning settlement.

It became a significant settlement in Britannia, and the Romans constructed all of the public buildings one would expect to find in a town of such importance—a forum, basilica, baths, an advanced sewerage system, statues, temples, and a public fountain.

Lindum Colonia fell out of favor when the Romans abandoned the frontier provinces, unable to keep the barbarians at bay throughout the empire. Roman troops were recalled from the island so they could be deployed throughout continental Europe.

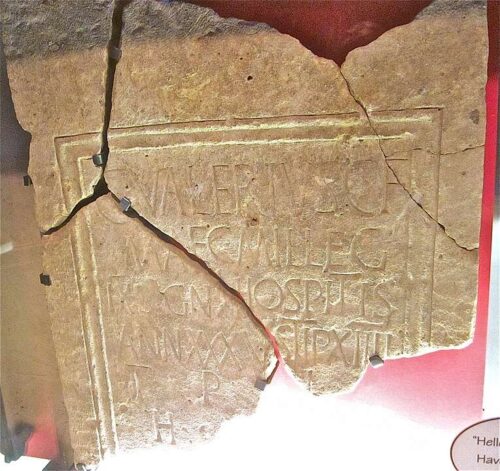

One of the most striking finds from Lindum Colonia was a tombstone of a Gaius Valerius, who was a standard bearer for Legio XI Hispana, who passed away not after the ninth legion arrived. He was 35 and served in the Roman army for 14 years. The best possible translation of the tombstone reads (as some fragments are missing):

“Gaius Valerius, son of Gaius, of the Maecian voting-tribe, soldier of the Ninth Legion, standard-bearer of the century of Hospes, aged 35, of 14 years’ service, left instructions in his will for this to be set up. Here he lies.”

Chester Amphitheater

The Roman amphitheater in Chester was constructed sometime in the mid-to-late first century AD, during the first decades of Roman occupation.

It is the largest amphitheater in Britain so far but has been rebuilt a few times during the Roman period. According to Chester – A virtual stroll around the walls, it looks to have been constructed by Legio II Adiutrix and rebuilt by Legio XX Valeria Victrix sometime in the AD 80s.

The final version of the amphitheater was built late in the third century AD. It measured 320 feet (98 meters) by 286 feet (87 meters) and could accommodate up to 8,000 spectators. The amphitheater was used for spectacles and gladiatorial fights.

As with most Roman buildings, the amphitheater was abandoned and left to dereliction when the Romans withdrew from Britannia. Most of the material was quarried for other buildings, while garbage was dumped there. It was eventually buried under centuries of erosion and earth being dumped here.

Only half of the amphitheater has been excavated, as the other half sits underneath heritage-listed buildings.

Eboracum (York)

Eboracum (York) was founded in AD 71, almost three decades after the Romans entered Britannia. The delay was caused by the land being occupied by the Brigantes, who became a client state of the empire.

Events saw those arrangements change, and eventually, Legio IX Hispana built a fortress after the legion made its way up from Lindum Colonia (Lincoln).

As a result of the new garrison, a settlement sprung up, with the injection of 5,000+ men into the area proving a boon for trade and business.

Due to its location and its importance as a frontier town, several emperors and future emperors visited Eboracum. The first was Hadrian, who was on his way to devising plans to construct his Wall.

Septimius Severus based himself there as he prepared for his Caledonian campaign. However, Severus died in Eboracum in AD 211. As noted by Cassius Dio in his book Roman History, Book LXXVII, XV:

“At all events, before Severus died, he is reported to have spoken thus to his sons (I give his exact words without embellishment): “Be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, and scorn all other men.” After this his body, arrayed in military garb, was placed upon a pyre, and as a mark of honor, the soldiers and his sons ran about it; and as for the soldiers’ gifts, those who had things at hand to offer as gifts threw them upon it, and his sons applied the fire. Afterward, his bones were put in an urn of purple stone, carried to Rome, and deposited in the tomb of the Antonines. It is said that Severus sent for the urn shortly before his death, and after feeling of it, remarked: “Thou shalt hold a man that the world could not hold.”

Emperor Constantius I also died in Eboracum in AD 306. He declared his son, Constantine, emperor to the armies of Britannia, who subsequently carried out the dying man’s wishes.

The decline of the Roman Empire in the fourth and fifth centuries AD saw a complete withdrawal of Roman forces from Britannia, leaving Roman settlements to the locals, which changed its usage over the following decades and centuries.

One of the ruins still visible is the Multangular Tower. The tower was located in the western part of the Roman fortress. Its base is Roman, but additions have been made during the medieval period. In the image below, the medieval additions are noticeable by the larger stones and the cross-shaped arrow slits.

Sources:

Historia Augusta – The Life of Hadrian (Thayer) – https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Historia_Augusta/Hadrian/1*.html#ref90

Cassius Dio – Roman History (Thayer) – https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/77*.html

Roman Inscriptions of Britain – https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/257

A Visual Stroll Around the Walls of Chester – https://chesterwalls.info/amphitheatre.html#top