The velites were a light infantry unit in the Roman military during the mid-Republican era. They existed for about a century before being disbanded.

The first recorded use of the velites was in 211 BC during the Siege of Capua when the Romans fought the invading Carthaginian army in the Second Punic War. Their lineage can be traced back to the earlier leves unit of the fifth century BC.

The velites were very lightly armored. The unit was comprised of the poorer citizens of Rome who could not afford proper armor. The unit also consisted of many youths keen to test themselves in combat.

They were typically armed with several javelins and also carried a small round shield (called a parma). The velites took on the role of skirmishers and were often stationed on the front line initially. The velites could then engage the enemy from a distance to either cause casualties or provoke the enemy into action.

In his book, The Histories, Book VI, XXI.VI, Polybius describes the velites and where they rank in the Roman legion and their number:

“The tribunes in Rome, after administering the oath, fix for each legion a day and place at which the men are to present themselves without arms and then dismiss them. When they come to the rendezvous, they choose the youngest and poorest to form the velites; next to them are made hastati, those in the prime of life principes, and the oldest of all triarii, these being the names among the Romans of the four classes in each legion distinct in age and equipment. They divide them so that the senior men known as triarii number six hundred, the principes twelve hundred, the hastati twelve hundred, the rest, consisting of the youngest, being velites. If the legion consists of more than four thousand men, they divide accordingly, except as regards the triarii, the number of whom is always the same”.

It is important to note that a Roman legion at the time typically consisted of 4,000 infantry and was usually topped up with cavalry. According to Polybius’ calculations, there were approximately 1,000 velites per legion.

Polybius then goes on to note how the velites were armed in Book VI, XXII:

“The youngest soldiers or velites are ordered to carry a sword, javelins, and a target (parma). The target is strongly made and sufficiently large to afford protection, being circular and measuring three feet in diameter. They also wear a plain helmet and sometimes cover it with a wolf’s skin or something similar both to protect and to act as a distinguishing mark by which their officers can recognize them and judge if they fight pluckily or not”.

Wearing animal skin helped the officers recognize who fought well in battle. This could then lead to an increase in pay for the soldier or a far more lucrative promotion within the Roman army.

The most famous battle in which the velites were used was the Battle of Zama against the Carthaginians during the Second Punic War. This battle ended the war and changed the course of not only the two ancient civilizations but also world history.

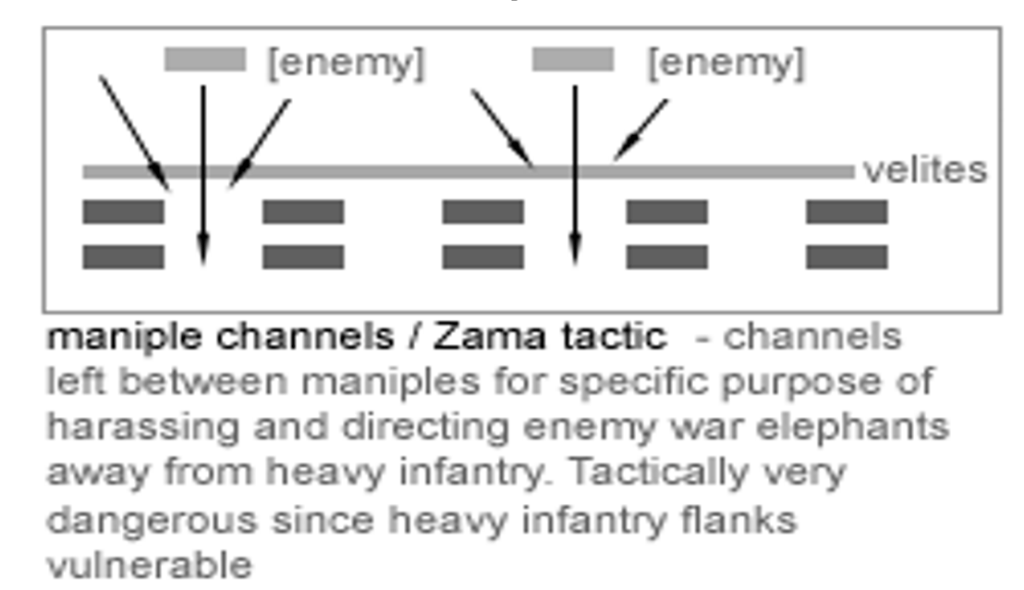

The velites were positioned in the front lines as usual, but the heavy infantry behind them was arranged in columns. The velites skirmished with the Carthaginian army, which then deployed its infamous war elephants.

The Romans (who notoriously had problems dealing with the elephants) deployed their own counter-tactic by having the velites retreat into the infantry columns behind them as the elephants bore down upon them. This allowed the Romans to channel the elephants between the columns and enabled them to cut down or drive out the beasts.

As Livy notes in his work, The History of Rome, Book XXX, XXXIII.XIV:

“A few of the animals, however, showed no fear and were urged forward upon the ranks of velites, amongst whom, in spite of the many wounds they received, they did considerable execution. The velites, to avoid being trampled to death, sprang back to the maniples and thus allowed a path for the elephants, from both sides of which they rained their darts on the beasts. The leading maniples also kept up a fusillade of missiles until these animals too were driven out of the Roman lines onto their own side and put the Carthaginian cavalry, who were covering the right flank, to flight.”

The velites also fulfilled specific roles within the Roman army when not in combat. When the army set up camp, the velites were typically posted to guard duty around the outer part of the camp.

As Polybius notes in Book VI, XXXV.V:

“The whole outer face of the camp is guarded by the velites, who are posted every day along the vallum — this being the special duty assigned to them — and ten of them are on guard at each entrance.”

The army’s reforms, typically dated to the late second century BC or early first century BC, saw many infantry units disbanded, including the velites, hastati, and principes. Light infantry units, such as the velites, were removed as a core unit from the Roman military, as the legions were turned into ones that focused on heavy infantry. Roman auxiliaries (allies or client states of Rome) fulfilled the role of light infantry. These reforms were attributed to General Gaius Marius, but this is disputed.

As noted by William Smith in his book, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1875), page DVI:

“The Velites disappeared. The skirmishers, included under the general term levis armatura, consisted for the most part of foreign mercenaries possessing peculiar skill in the use of some national weapon, such as the Balearic slingers (funditores), the Cretan archers (sagittarii), and the Moorish dartment (jaculatores). Troops of this description had, it is true, been employed by the Romans even before the second Punic war and were denominated levium armatorum (s. armorum) auxilia, but now the levis armatura consisted exclusively of foreigners, were formed into a regular corps under their own officers, and no longer entered into the constitution of the legion.”

The reforms led to a more efficient and professional army that conquered much of the known world.

Sources:

The Histories – Polybius (Thayer)

The History of Rome – Livy (Perseus Digital Library)

A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities – William Smith (Thayer)