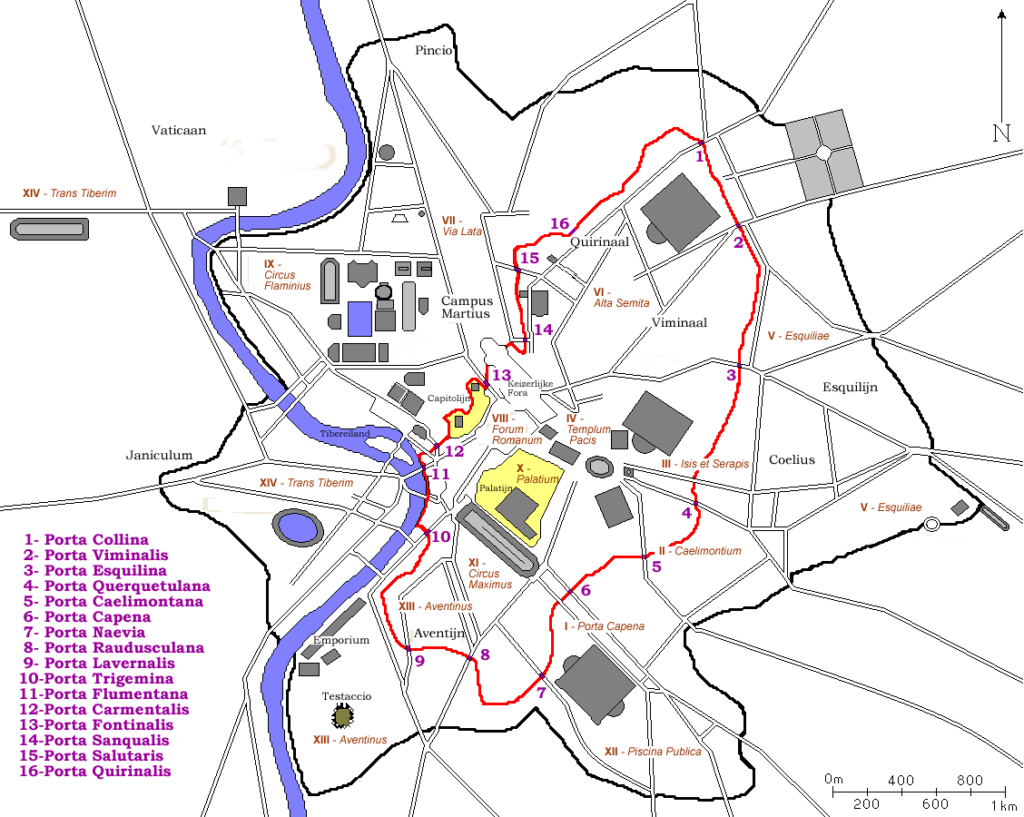

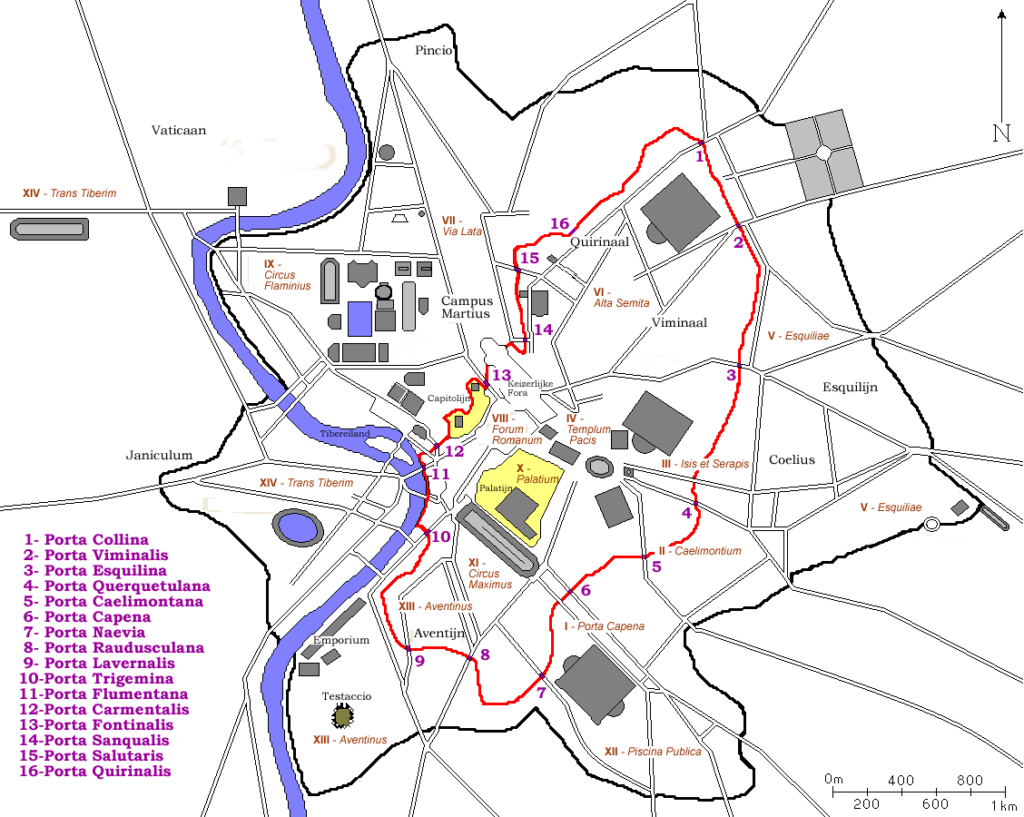

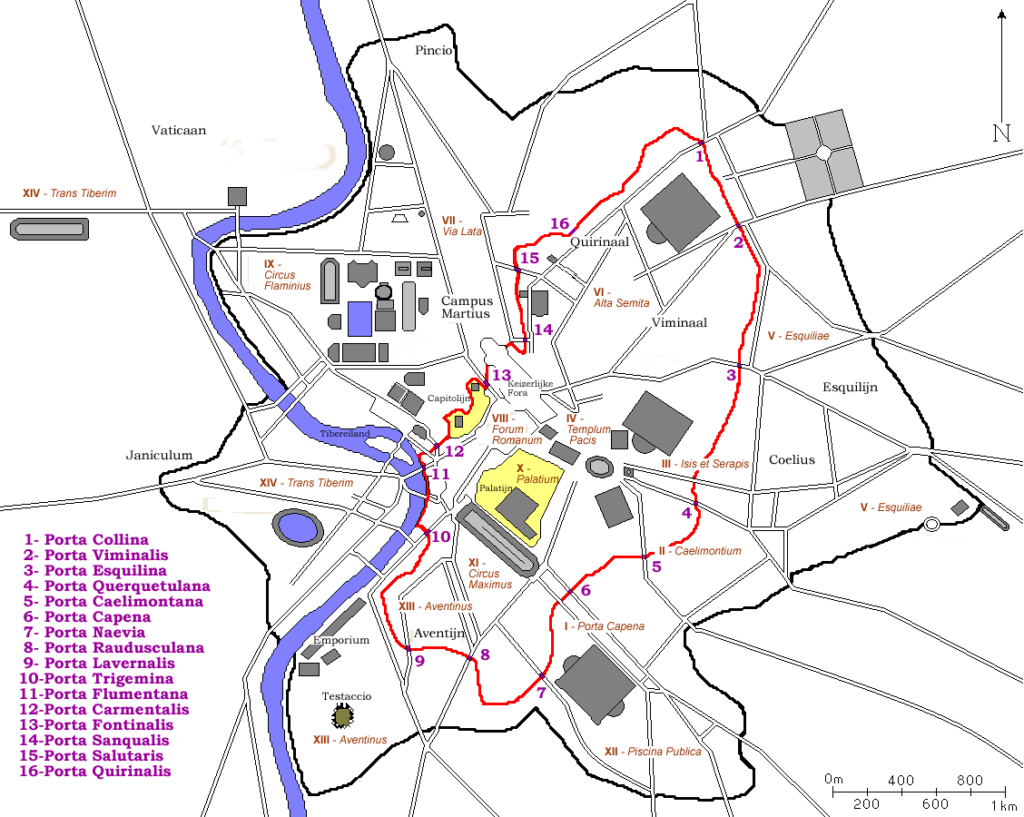

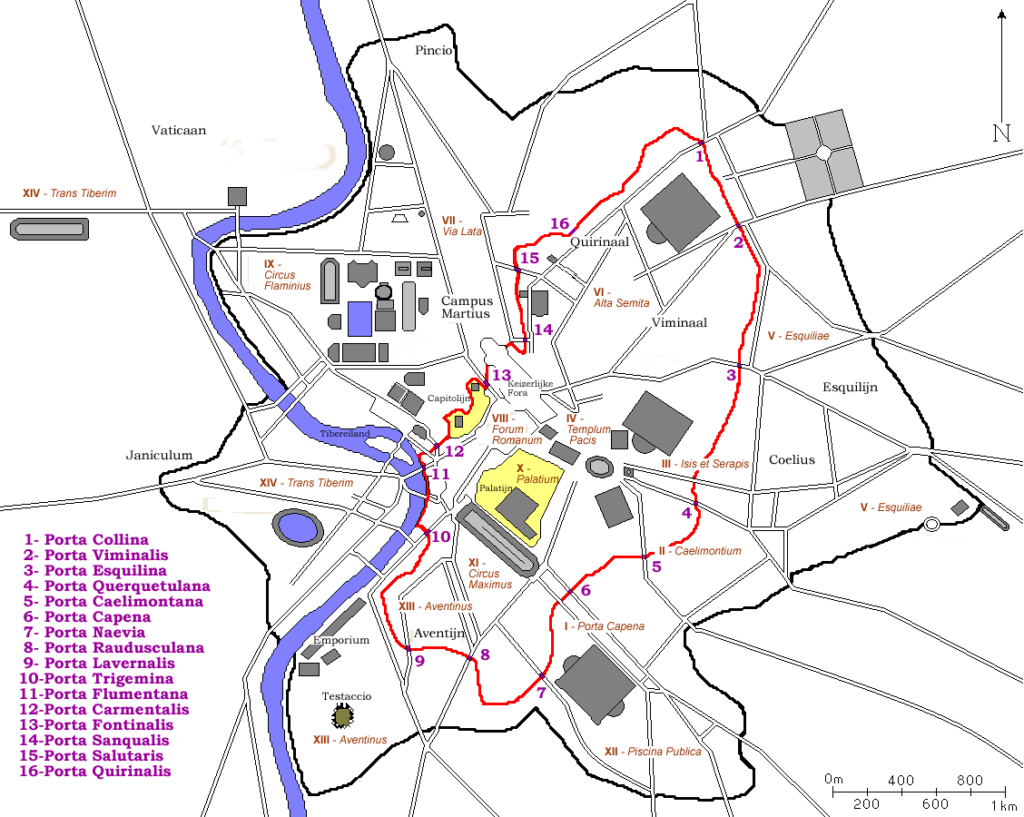

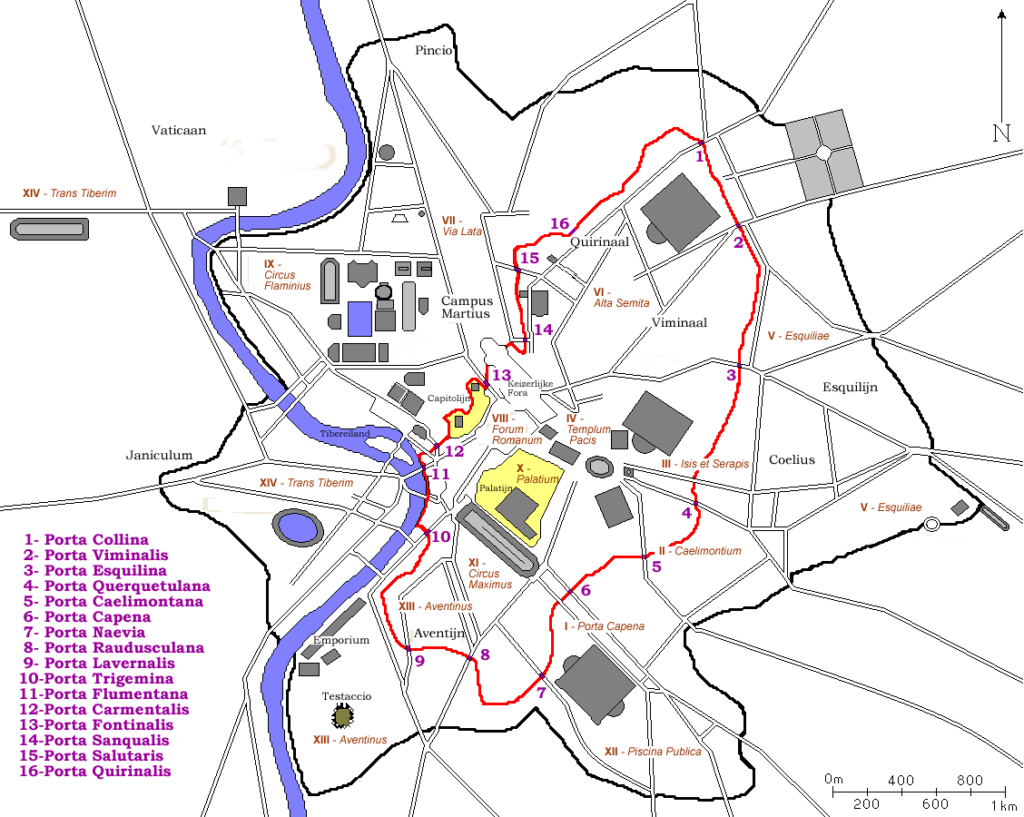

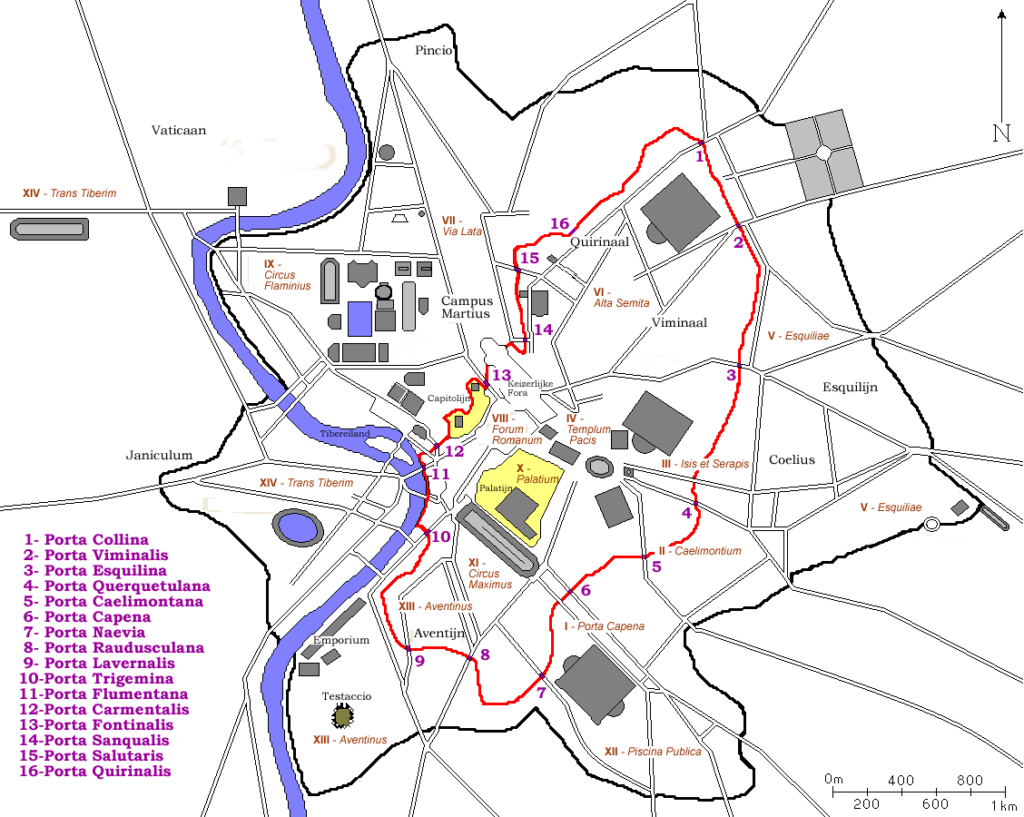

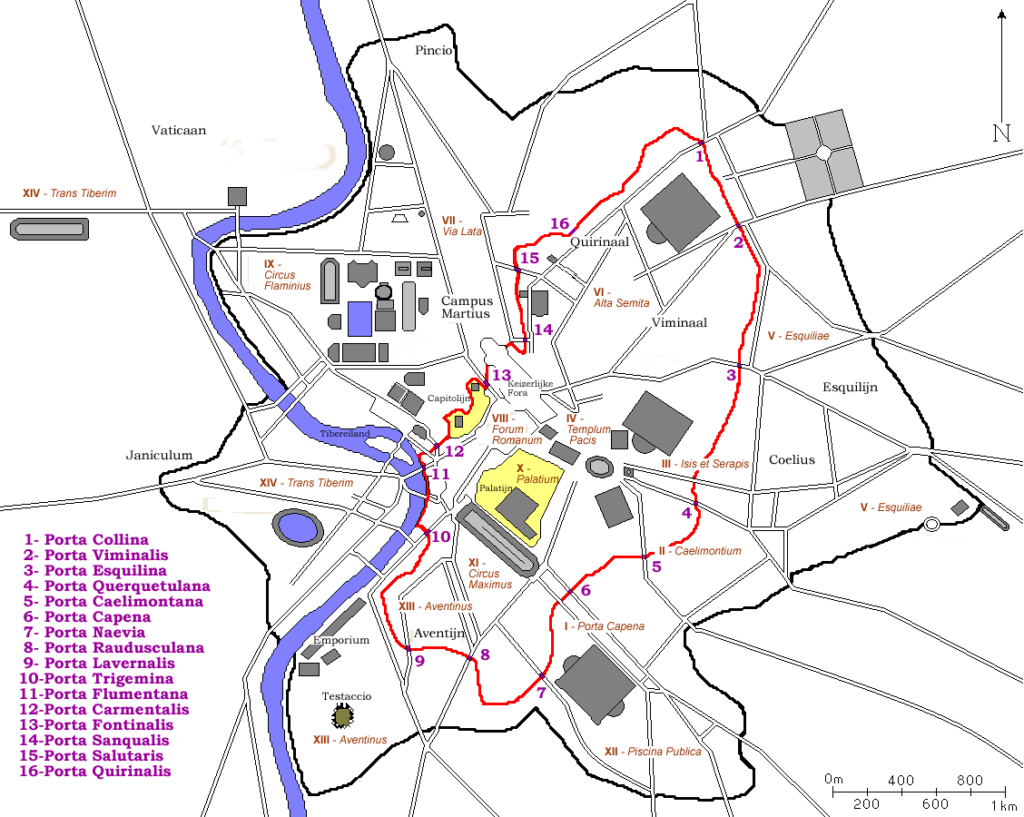

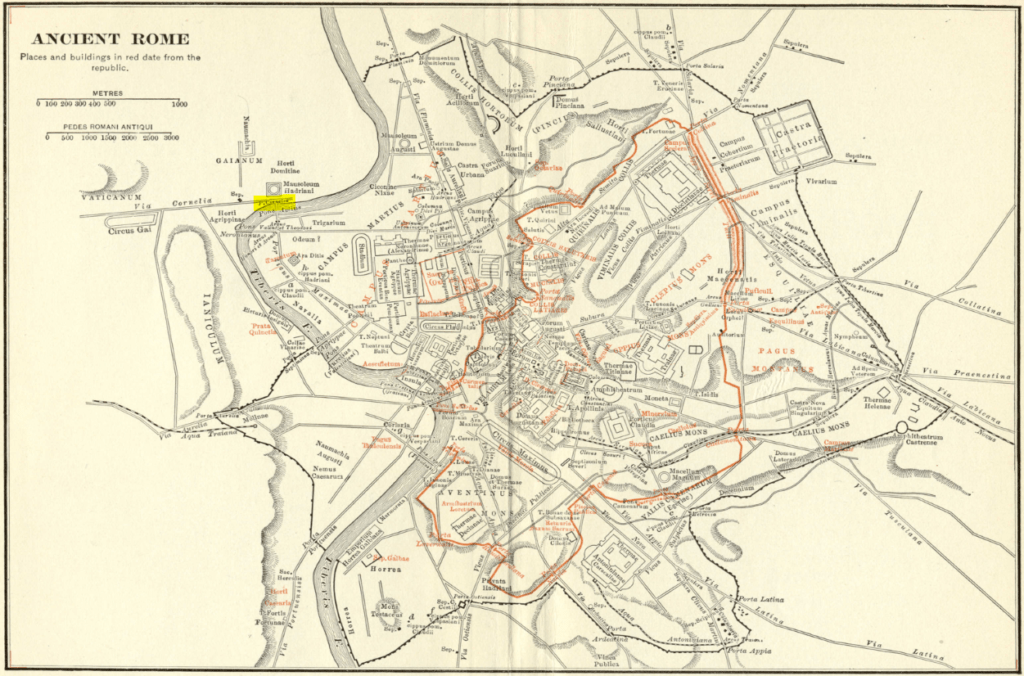

These are the gateways to the ancient city and, for a time, gates to the ancient civilization. First, we had gates that made up Rome’s first proper defensive structure – the Servian Wall. Emperor Aurelian built larger and longer walls late in the third century AD to protect the ever-growing city – the Aurelian Wall. Let’s take a look at 51 gates of ancient Rome.

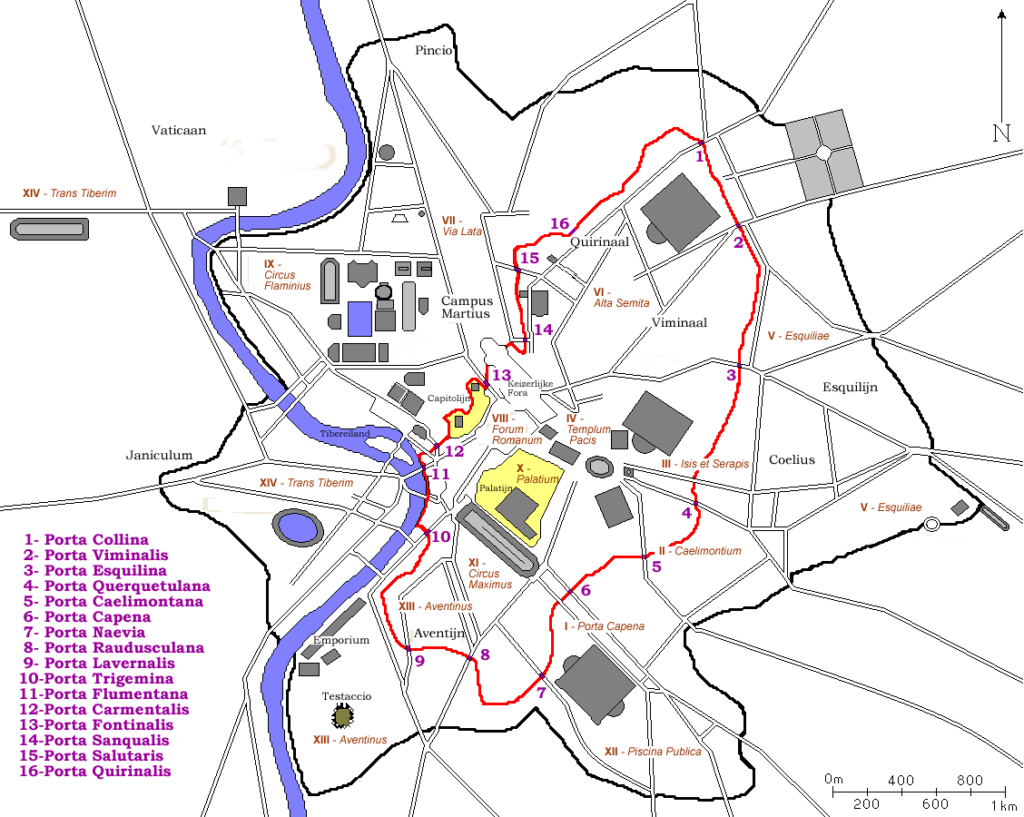

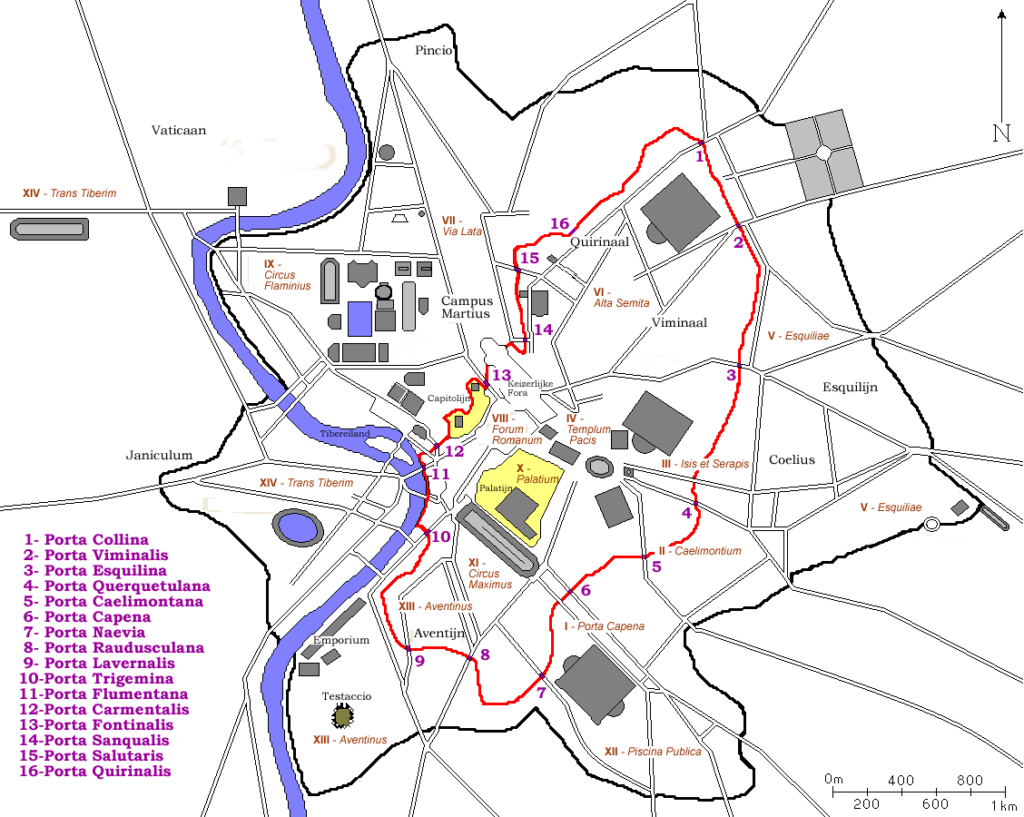

Gates of the Servian Wall

Porta Caelimontana

There has been some conjecture in modern times regarding the location of the Porta Caelimontana. Ancient sources have the Porta Caelimontana situated along the south-eastern side of the Servian Wall, near the intersection of the Via dei SS. Quattro and Via Santo Stefano Rotondo.

However, modern scholarship suggests that the Arch of Dolabella and Silanus is the rebuilt Porta Caelimontana, situated further west. This is where the Porta Querquetulana was roughly located. It is now suggested that the Porta Querquetulana was located where the Porta Caelimontana was initially thought to be located.

The Arch of Dolabella and Silanus (and, by extension, the Porta Caelimontana) still exists today.

By LPLT CC BY-SA 4.0

Porta Capena

The Porta Capena was a gate in southern Rome. This is the gate from which the Via Appia had initially started, long before the Porta Appia existed. Legend has it that the gate even pre-dated the building of the Servian Wall and the Roman Republic.

It is said that the gate’s original name was Porta Camena, but it was changed to Capena after construction started on the Via Appia. Capua was the Via Appia’s intended destination, so the gate’s name reflected the importance of this fact.

One of the earliest recorded usages of the gate was when the Romans fought the Volsci tribe in the early fifth century BC. The Volsci were driven out of Rome via the ‘Capuan gate.’ As noted by Dionysius of Halicarnassus in his book Roman Antiquities, Book VIII, IV:

“After the senate had passed this vote, some went through the streets making proclamations that the Volscians should depart from the city immediately and that they should all go out by a single gate, the one called the Capuan gate, while others, together with the consuls escorted them on their departure. And then particularly, when they went out of the city at the same time and by the same gate.”

The gate fell out of use during the second and third centuries AD when Emperor Caracalla leveled and redesigned the whole area, destroying the gate. As such, nothing remains of the old Porta Capena.

By fr:User:ColdEel & edited by nl:Gebruiker:Joris CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Carmentalis (Porta Scelerata/Porta Triumphalis)

The Porta Carmentalis was a double gate situated southwest of the Capitoline Hill.

Legend has it that the gate was named after the nymph Carmenta. Dionysius of Halicarnassus mentions the origin of Carmenta in his book, Roman Antiquities when the Greek expeditions landed in the area that was to become Rome. Book I, XXXI:

“Soon after, another Greek expedition landed in this part of Italy, having migrated from Pallantium, a town of Arcadia, about the sixtieth year before the Trojan war, as the Romans themselves say. This colony had for its leader Evander, who is said to have been the son of Hermes and a local nymph of the Arcadians. The Greeks call her Themis and say that she was inspired, but the writers of the early history of Rome call her, in the native language, Carmenta. The nymph’s name would be in Greek Thespiôdos or “prophetic singer”; for the Romans call songs carmina, and they agree that this woman, possessed by divine inspiration, foretold to the people in song the things that would come to pass.”

The naming of the gate seems fairly obvious, but it was confirmed by a few sources, including the poet Virgil in his Aeneid, book VIII, CCCXXXVII:

“He scarce had said, when near their path he showed an altar fair and the Carmental gate, where Romans see the memorial of Carmentis, nymph divine, the prophetess of fate, who first foretold what honors on Aeneas’ sons should fall and lordly Pallanteum, where they dwell.”

While Solinus notes in his work, On the Wonders of the World, chapter I, XII:

“The lowest part of the Capitoline mountain was also the dwelling of Carmenta, where Carmenta’s fanum is now, from which the name of the gate of Carmenta was given.”

The Porta Carmentalis comprised two individual gates, the Porta Scelerata, and the Porta Triumphalis. The Porta Scelerata was the arch on the right side as one left the city, and the Porta Triumphalis on the left.

The Porta Scelerata (the “Accursed Gate”) was named as such due to a military disaster that befell the Romans when a significant number of the Fabii family were killed in the war against the Veii. It is said that the Romans left the city through this particular gate, which was named after this disaster.

We know the name of the arch and which arch is which due to the meticulous nature in which the Romans kept written records of things. In Livy’s The History of Rome, book II, XLIX, he notes this as the Romans left the city:

“Their prayers were uttered in vain. Setting out by the Unlucky Way, the right arch of the Porta Carmentalis.”

However, there is some conjecture over this story. Scholars have noted that the gate may have been given the name due to the bodies of the dead being removed from the city and out to the Campus Martius.

The other gate that made up the Porta Carmentalis was the Porta Triumphalis. This is the gate where victorious generals would re-enter the city if they were awarded a triumph. This would mean that other people entering the city must enter via the Porta Scelerata. People exiting the city were forbidden to exit via the Porta Scelerata and instead exited through the Porta Triumphalis (yes, confusing, I know!)

There has also been some conjecture about this gate, with some suggesting that the name Triumphalis was a mere generic term given to any gate that a triumphant general passed through to get back into the city.

The Roman triumphal procession took place in the eastern part of the city. It included the Velabrum, Via Triumphalis, Circus Maximus, Via Sacra, and Forum Romanum before ascending the Capitoline Hill. The entry to the Circus Maximus for processions was said to be through the Porta Pompae, while a gate at the other end (Porta Triumphalis) was supposedly where the procession exited.

It could, therefore, be assumed that multiple gates were called Porta Triumphalis, or perhaps they were known as Porta Triumphalis, and then another name added to the end to describe which Porta Triumphalis someone was referring to (perhaps Porta Triumphalis Circenses for the gate at the Circus Maximus)

The Porta Carmentalis was rebuilt under Emperor Domitian in the last first century AD, with aesthetic details added. The gates are still visible today, but are no longer in use.

By Vadim Zhivotovsky, CC BY 3.0

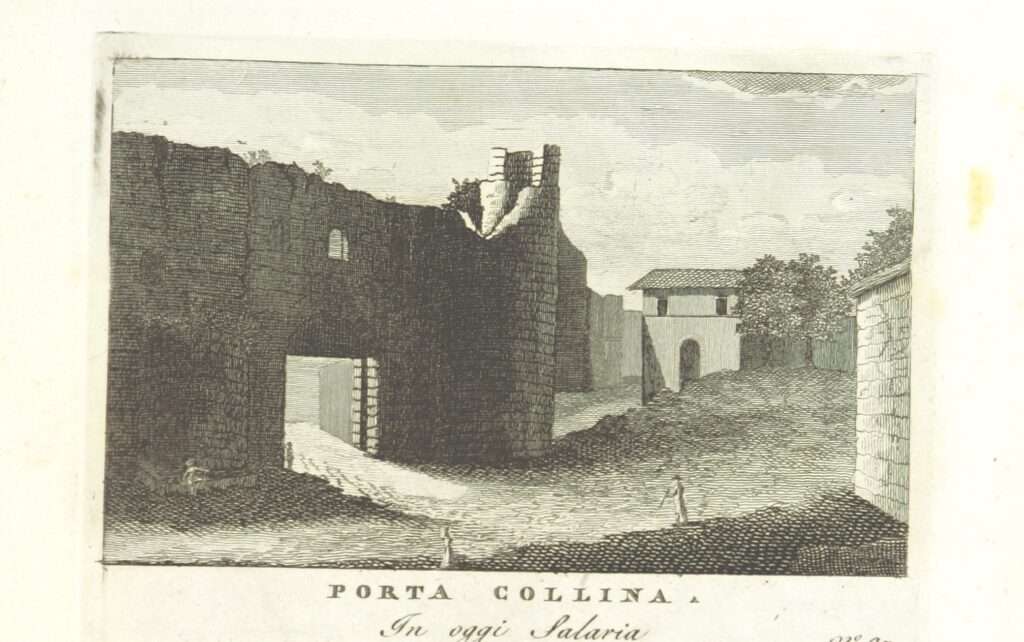

Porta Collina/Porta Agonensis

The Porta Collina was an ancient gate located in the northeast of Rome. This gate is where two important roads out of the city, the Via Salaria and Via Nomentana, began (before they were to eventually get their own gates when the Aurelian Walls were built).

The gate has been mentioned in narrations of a few battles in Republican times, suggesting that its location made it strategically advantageous to enemies or was seen as a weak spot in the city’s defenses.

Strabo suggests in his book, Geography, CCXXXIV.VII, that this part of the city and its surrounds was easy for enemy forces to attack, forcing Servius (builder of the Servian Wall) to dig a large trench on the outside of the wall, where he then used the earth as a rampart inside the wall:

“The first founders walled the Capitolium and the Palatium and the Quirinal Hill, which last was so easy for outsiders to ascend that Titus Tatius took it at the first onset, making his attack at the time when he came to avenge the outrage of the seizure of the maidens. Again, Ancus Marcius took in Mt. Caelium and Mt. Aventine and the plain between them, which were separated both from one another and from the parts that were already walled, but he did so only from necessity, for, in the first place, it was not a good thing to leave hills that were so well fortified by nature outside the walls for any who wished strongholds against the city, and, secondly, he was unable to fill out the whole circuit of hills as far as the Quirinal. Servius, however, detected the gap, for he filled it out by adding both the Esquiline Hill and the Viminal Hill. But these, too, are easy for outsiders to attack, and for this reason, they dug a deep trench and, took the earth to the inner side of the trench, and extended a mound of about six stadia on the inner brow of the trench, and built thereon a wall with towers from the Colline Gate to the Esquiline.”

Dionysius of Halicarnassus confirmed this weak point in his book, Roman Antiquities, LXVIII.III:

“One section, which is the most vulnerable part of the city, extending from the Esquiline gate, as it is called, to the Colline, is strengthened artificially. For there is a ditch excavated in front of it more than one hundred feet in breadth where it is narrowest and thirty in depth.”

Still, building fortifications was only one part of a city’s defense. This was highlighted by the Gallic Sack of Rome in 390 BC by Brennus of the Senones tribe. As Plutarch notes in his book, The Parallel Lives – The Life of Camillus, XXII.I, Brennus was surprised by the lack of resistance when he first entered the city:

“On the third day after the battle, Brennus came up to the city with his army. Finding its gates open and its walls without defenders, at first, he feared a treacherous ambush, being unable to believe that the Romans were in such utter despair. But when he realized the truth, he marched in by the Colline gate and took Rome.”

It is not known how much of the Roman Porta Collina still exists.

Porta Esquilina

The Porta Esquilina was located on the Esquiline Hill in the eastern part of the city. It was also located at the southern end of the agger (man-made trench) that was dug during the construction of the Servian Wall.

This is the gate in which the Via Labicana began before forking off and becoming the Via Labicana and Via Praenestina at the site of the future Porta Praenestina.

It appears to be a gate that was traditionally used in the killings of various people (possibly disposing of the bodies in the nearby agger). One such occasion was when the senate ruled that astrologers and ‘magic-mongers’ should be expelled from the country. As noted in the Annals by Tacitus, XXXII:

“Other resolutions of the senate ordered the expulsion of the astrologers and magic-mongers from Italy. One of their number, Lucius Pituanius, was flung from the Rock; another — Publius Marcius — was executed by the consuls outside the Esquiline Gate according to ancient usage and at sound of trumpet.”

It is the location of the Arch of Gallienus (which still survives), with the Porta Esquilina being turned into a triumphal arch. It was said that the arch had a smaller arch on either side of it, but they were demolished in later times.

By Tomk2ski CC BY-SA 4.0

Porta Flumentana

The Porta Flumentana was a gate located next to the Tiber River in the western part of the city. It was close to the Pons Aemilius.

Due to its location, it was prone to the flooding of the Tiber River. This was a common occurrence in ancient times. As noted by Livy in his book, The History of Rome, Book XXXV, IX.III:

“There were great floods that year, and the Tiber overflowed the flat parts of the City; around the Porta Flumentana, certain buildings even collapsed and fell.”

While Livy also recorded another occasion in Book XXXV, XXI.VI:

“The Tiber, attacking the city with a more violent rush than the year before, swept away the two bridges and many buildings, especially around the Porta Flumentana.”

The gate has not survived to the modern day (hardly surprising considering its proximity to a river that flooded with regularity!).

By fr:User:ColdEel & edited by nl:Gebruiker:Joris CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Fontinalis

We know very little about the Porta Fontinalis as many of its references from antiquity have not survived.

The Porta Fontinalis was located at the northern end of the Capitoline Hill and opened onto the Campus Martius, where the Via Flaminia began. One of the few references that point to the location of the Porta Fontinalis is in Livy’s The History of Rome, Book XXXV, X.XII:

“The aedileship of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus and Lucius Aemilius Paulus was notable that year; they condemned many grazers; out of the fines, they set up gilded shields on the roof of the temple of Jupiter, constructed one portico outside the Porta Trigemina, adding a wharf on the Tiber, and another portico from the Porta Fontinalis to the altar of Mars, where the way led into the Campus Martius.”

A tomb of a shoemaker from antiquity, Gaius Julius Helius, was unearthed in 1887 and included an epitaph that mentioned the Porta Fontinalis. Archeologist Rodolfo Lanciani notes this tomb in his works, Pagan and Christian Rome, Chapter VI, page CCLXXIV:

“Finally, I shall mention the tomb of a boot and shoemaker, which was discovered February 5, 1887, in the foundations of one of the new houses at the foot of the Belvedere. This excellent work of art, cut in Carrara marble, shows the bust of the owner in a square niche, above which is a round pediment. The portrait is extremely characteristic: the forehead is bald, with a few locks of short curled hair behind the ears, and the face shaven, except that on the left of the mouth, there is a mole covered with hair. The man appears to be of mature age but healthy, robust, and of rather stern expression.

Above the niche, two “forms” or lasts are represented, one of them inside a caliga. They are evidently the signs of the trade carried on by the owner of the tomb, which is announced in his epitaph: “Caius Julius Helius, shoemaker at the Porta Fontinalis, built this tomb during his lifetime for himself, his daughter Julia Flaccilla, his freedman Caius Julius Onesimus and his other servants.

The city’s expansion over the centuries meant that the Via Flaminia no longer led directly out of the modern city from the Porta Fontinalis, while the remains of the Porta itself have been lost to history.

By fr:User:ColdEel & edited by nl:Gebruiker:Joris CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Lavernalis

Not much is known about the Porta Lavernalis, except there is some contention about its location. This is mainly due to a lack of surviving information from the ancient sources.

It is generally considered that the Porta Lavernalis was located on the western side of the Aventine Hill, likely near the intersection of the modern Via di Porta Lavernale and the P.za dei Servili. It is said to have been named after the nearby altar and grove of Laverna.

However, there have been suggestions that the gate was located in the northern part of the city. With no remains and very little ancient evidence, the location of the gate at the Aventine Hill seems the most plausible.

By fr:User:ColdEel & edited by nl:Gebruiker:Joris CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Naevia

The Porta Naevia was another gate located at the Aventine Hill. We also have very little surviving information about this gate either.

It was likely located on the south-eastern side of the hill, with the Via Ardeatina running through it.

Nothing remains of the gate, and no place is immediately apparent where the gate might have stood.

By fr:User:ColdEel & edited by nl:Gebruiker:Joris CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Querquetulana

The other gate in the Porta Caelimontana/Porta Querquetulana confusion.

Older scholarship has the Porta Querquetulana situated on the western part of the Caelian Hill and the Porta Caelimontana roughly located in the middle of the Hill.

However, more modern scholarship has indicated that these gates were incorrectly named, and the names should be swapped. The Arch of Dolabella and Silanus is said to be the rebuilt Porta Caelimontana. If that is the case, then the Porta Querquetulana no longer exists, as there are no remains of a gate where it was thought to be located.

By fr:User:ColdEel & edited by nl:Gebruiker:Joris CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Quirinalis

The Porta Quirinalis is yet another gate about which we have little information (so much for the Romans being fastidious recorders of information!).

It was located on the western side of Quirinal Hill in the northern part of the ancient city. It was likely named after the Temple of Quirinus (Aedes Quirinus or Templum Quirinus).

Nothing remains of the gate, but it is likely located near the modern Via del Quirinale.

By fr:User:ColdEel & edited by nl:Gebruiker:Joris CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Raudusculana

The Porta Raudusculana is another gate located at the Aventine Hill.

It was said to be located in the depression of the Aventine Hill, between Aventinus Maior and Aventinus Minor. The modern-day location is somewhere near the Viale Aventino at P.za Albania. Some ancient battlements have survived and either made up part of the gate or (more likely) were located near the ancient gate.

There are several theories as to how the gate got its name, with one fabled story being recorded by Valerius Maximus in his Factorum et Dictorum Memorabilum Libri Novem, Book V, V.VI.III:

“As the praetor, Cippus was kneeling and coming out of the gate, a prodigy of a new and unheard-of kind befell him: for on his head they suddenly plucked out the horns of the wild beasts, and the answer was that he would be king if he returned to the city. Lest this should happen, he imposed a voluntary and permanent exile upon himself. A worthy piety, which, as regards solid glory, is preferred to seven kings. To witness the grace of the effigy of the head of the brass gate, through which he had passed, was enclosed and called Rauduscula.”

By Lalupa CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Salutaris

The Porta Salutaris was located on the western side of the Quirinal Hill, slightly southeast of the Porta Quirinalis.

The gate’s name is said to derive from the nearby Temple of Salus (Aedes Salutis or Templum Salutis). Some scholars place the gate at the upper end of the Via della Dataria, southwest of the temple.

By fr:User:ColdEel & edited by nl:Gebruiker:Joris CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Sanqualis

Yet another gate on the western side of the Quirinal Hill. The Porta Sanqualis was located south of the Porta Salutaris.

The gate was named after the Temple of Semo Sancus Dius Fidius (near the modern-day church of San Silvestro al Quirinale).

The Largo Magnanapoli in modern-day Rome is said to be the remains of the Servian Wall and was likely part of the Porta Sanqualis.

By Lalupa CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Trigemina

The Porta Trigemina is often mentioned in ancient sources, leaving us to believe it was an essential gate in Rome.

While the exact location is disputed, it was located between the Aventine Hill and the Tiber River. Dionysius of Halicarnassus mentions that the Porta Trigemina is situated near the Aventine Hill when writing about an altar where the Romans make sacrifices in his book, Roman Antiquities, XXXII.II:

“I have seen two altars that were erected, one to Carmenta under the Capitoline hill near the Porta Carmentalis, and the other to Evander by another hill, called the Aventine, not far from the Porta Trigemina.”

The most popular theories about its location include that it is underneath the church of Santa Sabina or around 50 meters south of the church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin.

The name is likely derived from a theory that the gate had three openings. However, some scholars have questioned whether this is another gate – the Porta Minucia. This is because a statue of Lucius Minucius was erected outside the gate around 438 BC. Some suggest that the name was changed to Porta Minucia. Livy notes where the statue was located in his book, The History of Rome, Book IV, XVI:

“Quinctius then commanded the man’s house to be pulled down, that the bare site might commemorate the frustration of his wicked purpose. The place was named Aequimaelium. Lucius Minucius was presented with an ox and a gilded statue outside the Porta Trigemina.”

By fr:User:ColdEel & edited by nl:Gebruiker:Joris CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Viminalis

The Porta Viminalis is considered one of the oldest gates in Rome, and some suggest it pre-dates the Servian Wall by some 200 years.

It was considered one of the most vulnerable gates in the city as it was located right in the middle of the Servian agger, which was a weak part of the city’s defenses. As Strabo notes in his book, Geography, Book V, III.VII, there were difficulties in securing the city in the Roman regal period. He also names the gates on the eastern side of the city:

“Again, Ancus Marcius took in Mt. Caelium and Mt. Aventine, and the plain between them, which were separated both from one another and from the parts that were already walled, but he did so only from necessity; for, in the first place, it was not a good thing to leave hills that were so well fortified by nature outside the walls for any who wished strongholds against the city, and, secondly, he was unable to fill out the whole circuit of hills as far as the Quirinal. Servius, however, detected the gap, for he filled it out by adding both the Esquiline Hill and the Viminal Hill. But these, too, are easy for outsiders to attack, and for this reason, they dug a deep trench and, took the earth to the inner side of the trench, and extended a mound about six stadia on the inner brow of the trench, and built thereon a wall with towers from the Colline Gate to the Esquiline. Below the center of the mound is a third gate bearing the same name as the Viminal Hill. Such, then, are the fortifications of the city, though they need a second set of fortifications.”

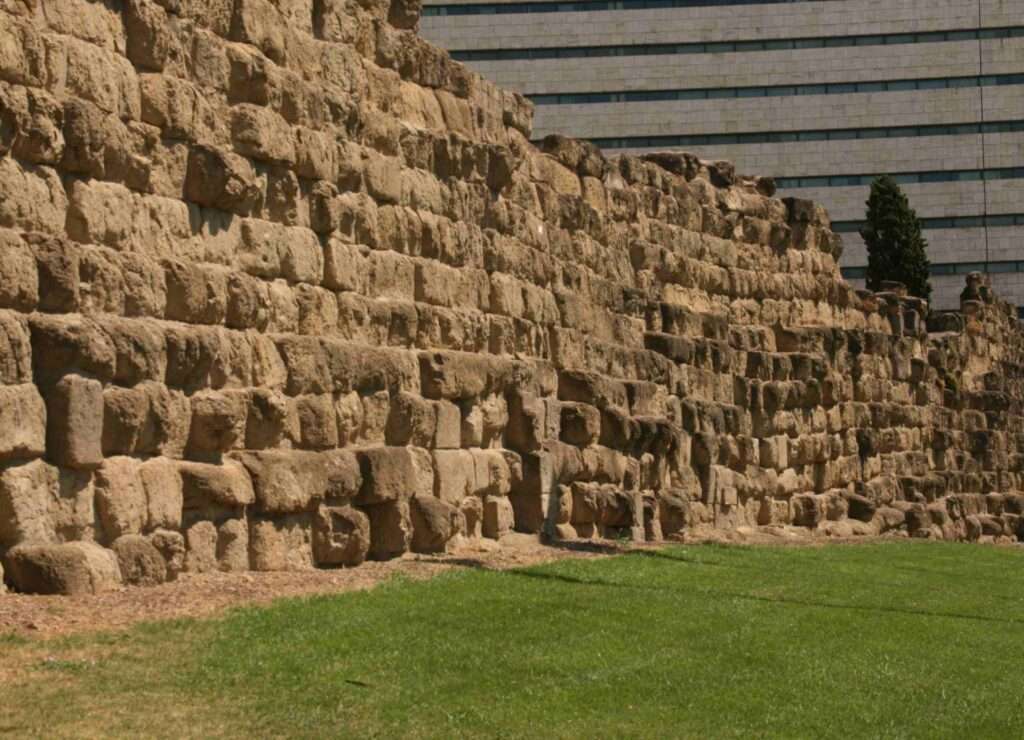

As you exit the modern-day Roma Termini railway station, off to the right is a large section of the Servian Wall, still intact. The gardens on the other side of the wall slope slightly towards the wall and are the remnants of the ancient Servian agger. While we do not know its exact location, the Porta Viminalis would not be far from the modern train station.

Gates of the Aurelian Wall

Porta Appia (Porta San Sebastiano)

The Porta Appia is a gate that is still in existence today but is known as Porta San Sebastiano.

Constructed as part of the Aurelian Wall building project, the wall dates to the late third century AD, during the reign of Aurelian (AD 270-275).

The Porta Appia straddles the famous Via Appia, the second gate to do so (the ancient Porta Capena is where the Via Appia starts as far as exiting the city is concerned).

The gate began life as a twin-arched gateway, but subsequent changes made it a single-arched gate.

Emperor Honorius improved the gate and the rest of the Aurelian Wall at the start of the fifth century AD. The walls and all of the gates were increased in height, and the height of the towers at Porta Appia reached 28 meters.

Several pieces of “graffiti” can be found on the gate’s façade, some in Greek and some in Medieval Latin. This shows the gate’s importance throughout history, as there appears to have been a lot of activity there throughout the centuries.

Porta Ardeatina/ Porta Laurentina

The Porta Adreatina is a Roman gate built during Emperor Nero’s reign.

As was the case with the construction project undertaken by Emperor Aurelian over two centuries later, to cut down on costs and time, many existing structures were incorporated into the Aurelian Walls. The fact that the gate sits at an unusual angle compared to the rest of the wall is a testament to this.

The Porta Adreatina is located in the southern part of the ancient city, close to its much more illustrious counterpart, the Porta Appia.

Emperor Honorius improved the gate at the start of the fifth century AD.

By Gustavo La Pizza CC BY-SA 4.0

Porta Asinaria

Located in the southeast of the ancient city, the Porta Asinaria was one of the few Aurelian-era gates that Honorius did not improve upon. It was, however, added to over the centuries, particularly during the Middle Ages.

With the nearby Porta San Giovanni being built in 1574, the Porta Asinaria was closed permanently to traffic as it had struggled over many years to keep up with the demands of the growing city.

The Porta Asinaria does hold a significant place in history as the place where Eastern Roman general Belisarius entered Rome, thus re-capturing the city from the Goths. As Procopius notes in his book, The Gothic Wars, Book I, XIV.XIV:

“And it so happened on that day that at the very same time when Belisarius and the emperor’s army were entering Rome through the gate which they call the Asinarian Gate, the Goths were withdrawing from the city through another gate which bears the name Flaminian; and Rome became subject to the Romans again after a space of sixty years, on the ninth day of the last month, which is called “December” by the Romans, in the eleventh year of the reign of the Emperor Justinian.”

The Porta Asinaria has survived almost entirely intact.

Porta Aurelia (Pancrazio)

The Porta Aurelia (Pancrazio) was a gate at the city’s western edge. Emperor Aurelian built it at the foot of Janiculum Hill. It goes by the name Porta San Pancrazio, but none of the original Porta Aurelia exists.

The Via Aurelia used to run through the Porta Aurelia after starting further east at the Pons Aemilius. The Via Aurelia (now Via Aurelia Antica) now starts at the modern Porta San Pancrazio.

By LPLT CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Aurelia-Sancti Petri/Porta Cornelia

The Porta Aurelia (Sancti-Petri) was originally known as the Porta Cornelia. The Via Cornelia started from this gate on the northern side of the Pons Aelius.

It is unclear exactly when the name was changed, but we know it was known as an “Aurelian Gate” (Porta Aurelia), at least by the sixth century AD through the writings of Procopius. In his book, The Gothic Wars, Book I, XIX.IV, he makes a distinction between both Aurelian gates (with the Porta Aurelia Pancraziana named the “Transtiburtine Gate” and the Porta Aurelia Sancti Petri being the one named after Peter):

“So in this way, two other gates came to be exposed to the attacks of the enemy, the Aurelian (which is now named after Peter, the chief of the Apostles of Christ, since he lies not far from there) and the Transtiburtine Gate.”

Emperor Honorius converted the Mausoleum of Hadrian into the Castel Sant’Angelo in the early fifth century, and the Porta Cornelia was incorporated into the Castel. The gate was then destroyed in the Middle Ages.

Public domain

Porta Clausa/Porta Chiusa

The name Porta Clausa/Porta Chiusa is rather modern, as the original name is not known.

The wall was located in the northeast of the city, acting as the southern gate of the Castra Praetoria. It pre-dates the Aurelian Wall of the third century AD.

It survived Emperor Constantine’s demolition of the Castra Praetoria in the fourth century AD but fell out of favor in the early Medieval period. Over the centuries, it may have been incorporated into another building or simply buried, but much of it has survived to this day.

By Joris CC BY-SA 2.5

Porta Flaminia

The Porta Flaminia was the ancient name for the modern Porta del Popolo.

The gate was located in the northern part of the city. Its name is derived from the Via Flaminia, which began at the Porta Fontinalis at the Servian Wall, went through the Campus Martius, through the Porta Flaminia, and out of the city.

This is the gate that the Goths fled Rome through when Belisarius entered the city during the Gothic Wars. Procopius notes in his book, The Gothic Wars, Book I, XIV.XIV:

“When Belisarius and the emperor’s army were entering Rome through the gate which they call the Asinarian Gate, the Goths were withdrawing from the city through another gate which bears the name Flaminian.”

The current Porta del Popolo was built on top of the site of the Porta Flaminia in 1475 by Pope Sixtus IV. Its importance ebbed and flowed over the centuries, while the Porta underwent many changes over the same period.

After demolition works carried out in 1879, workers discovered parts of the ancient structure of the Aurelian period. Stones from an earlier period were also found nearby.

By Chabe01 CC BY-SA 4.0

Porta Latina

The Porta Latina was located in the southern part of the ancient city. Its name comes from the Via Latina, which runs through it.

The Porta Latina survives to this day, with the current structure dating to the time of Emperor Honorius.

It had been closed at various times throughout its history, with 1827 being one of the last times it was closed. According to the British School of Rome, in their publication, Papers of the British School at Rome, Book IV, page XIII:

“The Via Latina diverged from the Via Appia 830 meters outside the Porta Capena (from which the mileage along it was measured), and after 500 meters more passed through the Porta Latina of the Aurelian Wall, a well-preserved gate (closed for the last time in 1827) reconstructed by Honorius.”

By Gustavo La Pizza CC BY-SA 4.0

Porta Metronia

The Porta Metronia is another gate in the southern part of ancient Rome. Over time, its spelling has varied, including Metrovia, Metrobi, Metroni, and Metrosi.

This was another bridge that was closed, this time in the Middle Ages. However, due to increased traffic, the gate was re-opened. Other openings were also made next to the original gate, but the original gate remains.

By Rabax63 CC BY-SA 4.0

Porta Nomentana

Located in the northeast of the ancient city is the Porta Nomentana. It is located just north of where the Castra Praetoria was located. The Via Nomentana passed through this gate.

Emperor Honorius upgraded the gate in the early fifth century, and Pope Pius IV added an arch in 1564. However, in 1565, the Via Nomentana was diverted to pass through the newly constructed Porta Pia, effectively rendering the Porta Nomentana obsolete.

With part of the gate being demolished in the nineteenth century, the rest of the Porta Nomentana was bricked up and simply became part of the walls of the site of the British Embassy.

By Gustavo La Pizza CC BY-SA 4.0

Porta Ostiensis – east (Porta San Paolo)

The Porta Ostiensis was a gate located in the southeast of ancient Rome.

This gate is where the Via Ostiensis ran through and straight down to the port town of Ostia. The modern Via Ostiense still follows the ancient route from the Aurelian-era gate to Ostia.

This was an important road for the Romans as grain, olive oil, and other goods were transported from ships docked at the port town to the ancient capital. As noted by Ammianus Marcellinus in his book, The Roman History, Book XVII, IV.XIV, Egyptian obelisks were also transported the same way:

“the obelisk was loaded on the ship, after long delay, and brought over the sea and up the channel of the Tiber, which seemed to fear that it could hardly forward over the difficulties of its outward course to the walls of its foster-child the gift which the almost unknown Nile had sent. But it was brought to the vicus Alexandri, distant three miles from the city. There, it was put on cradles and carefully drawn through the Ostian Gate and by the Piscina Publica and brought into the Circus Maximus.”

The obelisk, now known as the Lateran Obelisk, is located in the southwestern part of the ancient city just outside the Lateran Palace.

The name was changed to Porta San Paolo due to the nearby Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls. It is unclear when this name change occurred, but the new name was used in the sixth century AD, as Procopius notes in The Gothic Wars, Book III, XXXVI.VII:

“After the siege of Rome had continued for a long time, some of the Isaurians who were keeping guard at the gate which bears the name of Paul the Apostle.”

The Porta Ostiensis remains in excellent condition to this day.

By Livioandronico2013 CC BY-SA 4.0

Porta Ostiensis – west

The Porta Ostiensis (west) was located in the southeast of the ancient city, not far from its illustrious twin, Porta Ostiensis (east). It is doubtful that both gates would have had the same name and were only differentiated by “east” and “west.”

According to the book A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (1992), author Lawrence Richardson writes that there were two Porta Ostiensis gates, an east and a west gate. On page CCCV, he notes this about the Porta Ostiensis (west) gate:

“This gate, just west of the Pyramid of Cestius, was demolished in 1888, but Lanciani measured and drew it during the process. It was a small postern, 3.60m wide, serving the traffic to the large quarter of warehouses on the adjacent Tiber bank. The gate was faced with travertine and trimmed on the jambs and lintel with moldings. It was bricked up in the time of Maxentius and never re-opened. Because the road through it joined the Via Ostiensis only a little distance outside the walls, it was easy enough to link the two when the gate was abandoned.”

It appears that this gate was smaller and was used mainly for transporting warehouse goods rather than regular foot traffic.

Unlike its twin to the east, no remnants remain of this gate.

By MumblerJamie CC BY-SA 2.0

Porta Pinciana

The Porta Pinciana is located in the northern part of the ancient city.

It was originally built as a minor entrance into the city as it helped serve the Via Salaria. It was then expanded by Emperor Honorius in the early fifth century AD, turning it into a proper city gate.

The northern gates of Rome, including the Porta Pinciana, saw plenty of action during the Gothic Wars in AD 537. Roman general Belisarius and his troops took up defensive positions at the northern gates of the ancient city.

Sixth-century AD historian Procopius covered the Gothic Wars in some detail. His book provides invaluable insight into the ancient world after the ‘fall’ of the Western empire.

In Book I, XIX.XIV, he goes into detail about how Belisarius defended the city against the besieging Goths:

“And Belisarius arranged for the defense of the city in the following manner. He himself held the small Pincian Gate and the gate next to this on the right, which is named the Salarian. For at these gates the circuit-wall was assailable, and at the same time it was possible for the Romans to go out from them against the enemy. The Praenestine Gate he gave to Bessas. And at the Flaminian, which is on the other side of the Pincian, he put Constantinus in command, having previously closed the gates and blocked them up most securely by building a wall of great stones on the inside, so that it might be impossible for anyone to open them. For since one of the camps was very near, he feared lest some secret plot against the city should be made there by the enemy. And the remaining gates he ordered the commanders of the infantry forces to keep under guard. And he closed each of the aqueducts as securely as possible by filling their channels with masonry for a considerable distance to prevent anyone from entering through them from the outside to make mischief.”

The blocking-up of the aqueducts was a stroke of genius by Belisarius as the Goths tried to use the aqueducts to gain entry into the city. As Procopius notes in Book II, IX.I:

“And the Goths, not long after this, wished to strike a blow at the fortifications of Rome. And first, they sent some men by night into one of the aqueducts, from which they themselves had taken out the water at the beginning of this war. And with lamps and torches in their hands, they explored the entrance into the city by this way. Now it happened that not far from the small Pincian Gate, an arch of this aqueduct had a sort of crevice in it, and one of the guards saw the light through this and told his companions, but they said that he had seen a wolf passing by his post. For at that point it so happened that the structure of the aqueduct did not rise high above the ground, and they thought that the guard had imagined the wolf’s eyes to be fire. So those barbarians who explored the aqueduct, upon reaching the middle of the city, where there was an upward passage built in olden times leading to the palace itself, came upon some masonry there which allowed them neither to advance beyond that point nor to use the ascent at all. This masonry had been put in by Belisarius as an act of precaution at the beginning of this siege, as has been set forth by me in the preceding narrative. So they decided first to remove one small stone from the wall and then to go back immediately, and when they returned to Vittigis, they displayed the stone and reported the whole situation. And while he was considering his scheme with the best of the Goths, the Romans who were on guard at the Pincian Gate recalled among themselves on the following day the suspicion of the wolf. But when the story was passed around and came to Belisarius, the general did not treat the matter carelessly but immediately sent some of the notable men in the army, together with the guardsman Diogenes, down into the aqueduct and bade them investigate everything with all speed. And they found all along the aqueduct the lamps of the enemy and the ashes which had dropped from their torches, and after observing the masonry where the stone had been taken out by the Goths, they reported to Belisarius. For this reason, he personally kept the aqueduct under close guard, and the Goths, perceiving it, desisted from this attempt.”

The Porta Pinciana must have appeared to be a weak spot in the city’s fortifications as the Goths tried on several other occasions to break into it. Perhaps the writer focused on this gate more because this is where Belisarius was stationed.

The Porta was closed and re-opened many times over the centuries, but it has survived, is open, and is still in use.

By Gustavo La Pizza CC BY-SA 4.0

Porta Portuensis/ Porta Portese

Located on the other side of the Tiber, the Porta Portuensis was located in the southwestern part of the ancient city.

Built by Aurelian and improved upon by Honorius, the gate was twin-arched with semi-circular brick towers, like many of the other gates of the city.

One arch was filled in later before being destroyed by Pope Urban VIII sometime during his reign (AD 1623-1644). It was replaced by the Porta Portese, located around a third of a mile (453 meters) closer to the city.

The seventeenth-century gate still stands to this day.

By Gustavo La Pizza CC BY-SA 4.0

Porta Praenestina/ Porta Labicana/ Porta Maior (Porta Maggiore)

The Porta Praenestina/Porta Labicana, now known as the Porta Maggiore, is located on the eastern side of ancient Rome.

It was a double-arched structure that spanned the Via Praenestina and Via Labicana. It was part of the support structure for the aqueducts Aqua Claudia and Anio Novus.

Emperor Claudius built it in AD 53, completing the aqueduct project started by his predecessor, Emperor Caligula.

As these arches span two different roads (with each going in a different direction), the arches are at slight angles to one another. As such, these gates were known by their separate names – Porta Praenestina and Porta Labicana. This is likely to give a more accurate description of which gate is being talked about and also to specify which road one was referring to when talking to others (instead of saying road on the left or road on the right, etc).

Emperor Aurelian incorporated the Porta Praenestina into the Aurelian Walls when they were built in the late third century AD as part of his plan to incorporate existing structures into defensive fortifications. Emperor Honorius also made improvements at the start of the fifth century AD.

Located just outside the Porta Praenestina/Labicana was a late republican-era tomb of Eurysaces the baker. Honorius incorporated this tomb into his improvements of the fortifications of the city. As noted in the Papers of the British School at Rome in 1902, page CXXX:

“Honorius closed the left-hand aperture, leaving only the right-hand one opened, and building a tower upon the tomb of Eurysaces the baker, which stood, as its peculiar shape shows, at the point where the roads separated. This tomb, which belongs to the last century of the Republic, was exposed to view in 1838 when the tower of Honorius was removed.”

The Porta Maggiore is still in use today.

By Joris, CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Salaria

The Porta Salaria was a gate located in the northeast of the ancient city and played a significant role in the Gothic Wars of the sixth century AD.

As noted by Procopius in his book, The Gothic Wars, the Roman army was fighting the Goths outside the city but was losing the battle. As they were retreating, they came to the Porta Salaria, but the scared Roman citizens would not let them in as they were unsure if the soldiers were friends or foes. Book I, XVIII.XIX:

“In this way, the Romans escaped and arrived at the fortifications of Rome, and the barbarians, in pursuit, pressed upon them as far as the wall by the gate which has been named the Salarian Gate. But the people of Rome, fearing lest the enemy should rush in together with the fugitives and thus get inside the fortifications, were quite unwilling to open the gates, although Belisarius urged them again and again and called upon them with threats to do so. For, on the one hand, those who peered out of the tower were unable to recognize the man, for his face and his whole head were covered with gore and dust, and at the same time, no one was able to see very clearly, either; for it was late in the day, about sunset. Moreover, the Romans had no reason to suppose that the general survived, for those who had come in flight from the rout which had taken place earlier reported that Belisarius had died fighting bravely in the front ranks.”

Upon entering the city, Belisarius proceeded to check all of the gates and fortifications of the city, assigning commanders to the gates, particularly along the northern section of the city. As for Belisarius himself, according to Procopius in Book I, XIX.XIV:

“And Belisarius arranged for the defense of the city in the following manner. He himself held the small Pincian Gate and the gate next to this on the right, which is named the Salarian. For at these gates the circuit-wall was assailable, and at the same time it was possible for the Romans to go out from them against the enemy. The Praenestine Gate he gave to Bessas. And at the Flaminian, which is on the other side of the Pincian, he put Constantinus in command, having previously closed the gates and blocked them up most securely by building a wall of great stones on the inside, so that it might be impossible for anyone to open them.”

The Goths then staged an assault on the city. They were advancing with siege towers and rams. Belisarius remained patient, not attacking straight away, much to the dismay of the Roman citizens. After a few shots from his own bow and killing a number of Goths, he finally gave the signal for the rest of the army to fire their arrows, as the enemy was relatively close by this time. All of this occurred at the Porta Salaria. As recorded by Procopius in Book I, XXII.VII:

“Then Belisarius gave the signal for the whole army to put their bows into action, but those near himself he commanded to shoot only at the oxen. And all the oxen fell immediately so that the enemy could neither move the towers further nor, in their perplexity, do anything to meet the emergency while the fighting was in progress. In this way, the forethought of Belisarius in not trying to check the enemy while still at a great distance came to be understood, as well as the reason why he had laughed at the simplicity of the barbarians, who had been so thoughtless as to hope to bring oxen up to the enemy’s wall. Now, all this took place at the Salarian Gate.”

In more modern times, the Porta Salaria was severely damaged when the final battle of the Italian re-unification took place in 1870. The gate was demolished soon after before being rebuilt in 1873. That gate was then demolished in 1921. The area is now the Piazza Fiume, where the old Roman walls can still be seen.

By Carlo Dani CC BY-SA 4.0

Porta Septimiana (Porta Settimiana)

The Porta Septimiana (now known as Porta Settimiana) is located on the western side of the ancient city, on the other side of the Tiber.

There is little mention of it in ancient sources. The most likely theory is that the gate took its name from Emperor Septimius Severus.

The book Historia Augusta – The Life of Septimius Severus mentions some building works that were completed during the emperor’s reign, including a gate to the city. XIX.V:

“The principal public works of his now in existence are the Septizonium and the Baths of Severus. He also built the Septimian Baths in the district across the Tiber near the gate named after him, but the aqueduct fell down immediately after its completion, and the people were unable to make any use of them.”

It was rebuilt and improved on several occasions throughout history; however, the current gate does not date back to Roman times.

By jeffwarder, CC BY-SA 3.0

Porta Tiburtina/Porta Taurina (Porta San Lorenzo)

The Porta Tiburtina/Porta Taurina (now known as Porta San Lorenzo)is a gate on ancient Rome’s east side.

It began life as an arch, built under Emperor Augustus in 5 BC, with modifications made by Emperor Aurelian and Emperor Honorius. The incorporation of the arch into the Aurelian Wall converted it into a gate to the city.

The gate received the name (perhaps a nickname) Porta Taurina due to the images of bulls on the arch/gate’s keystones.

The gate was also located at the convergence of three aqueducts: the Aqua Marcia, Aqua Julia, and Aqua Tepula.

The gate still exists today but is closed to all traffic. However, Pope Pius IX removed much of the Roman material from the gate itself. It is unclear how much of the Roman gate remains, besides possibly the towers that flank it.

Gates of the Regal period/Miscellaneous gates

Porta Mugonia (Mucionia/Mucionis)/Porta Vetus Palatii

The Porta Mugonia was one of the oldest gates in Rome, dating back to the time of Romulus. It was also known as the Porta Palatii.

It was located on the Palatine Hill, where the ancient civilization first began its life. It is located on the north side of the hill, not far from the temple of Jupiter Stator. Dionysius of Halicarnassus gives a bit more detail on the location of the gate in his Roman Antiquities, Book II, L.III:

“They built temples also and consecrated altars to those gods to whom they had addressed their vows during their battles: Romulus to Jupiter Stator, near the Porta Mugonia, as it is called, which leads to the Palatine hill from the Sacred Way.”

This suggests that the gate was located on the northeastern side of the hill, as that is nearest to the Via Sacra.

As expected, nothing remains of this ancient gate.

Porta Pandana/ Porta Saturnia

The Porta Pandana was located on the Capitoline Hill during Rome’s formative years. In fact, the Capitoline was previously called Mons Saturnius, which is where its alternate name of Porta Saturnia comes from. As noted by Gaius Julius Solinus in his works, On the Wonders of the World, Book I, line XIII:

“Even the house which is said to be Saturn’s treasure-house, was built by his companions in honor of Saturn, whom they knew to have been the worshiper of that region. They also named the Capitoline Hill Saturnus. The castles also, which they had raised, addressed the gate of Saturnia, which afterwards was called Pandana.”

This is said to have been the gate that Tarpeia opened to let the Sabines in, which subsequently led to her being thrown off the cliff that then bared her name, the Tarpeian Rock.

The gate no longer exists.

Porta Romana/Porta Romanula

One of the ancient gates of Rome, speculation abounds when it comes to the location of the Porta Romana.

Some ancient sources have the gate located at the northwest corner of the Palatine Hill, others at the foot of the Palatine Hill, while it has also been speculated that it is located off the Palatine Hill near the Church of San Teodoro.

Scholars have had difficulty determining its likely location because gates are usually named after an important street that leads from it or an important landmark nearby. However, this gate is named after Rome itself, so it doesn’t narrow down the details.

Porta Ianualis

There is some dispute about whether the Porta Ianualis was actually a gate.

The gates were said to be sacred gates that remained open when Rome was at war and closed during times of peace. They were closed during the entirety of King Numa’s reign (the successor to Romulus) and opened and closed a number of times throughout Roman history.

It was located north of the Palatine Hill, but its exact location is unknown. It is suggested that somewhere near the Temple of Vesta.

Some sources record the Porta Ianualis as a gate leading to the temple of Janus (Ianus Geminus), while others have suggested that the doors to the temple itself were gates. There is also a theory that there was no temple, and the gates were an arch, which became a symbolic entrance into a forum.

Plutarch alludes to the theory that the Porta Ianualis were double doors to the temple Ianus Geminus, as he notes in his book, The Parallel Lives – The Life of Numa, XIX.VI:

“For this Janus, in remote antiquity, whether he was a demi-god or a king, was a patron of civil and social order and is said to have lifted human life out of its bestial and savage state. For this reason, he is represented with two faces, implying that he brought men’s lives out of one sort and condition into another. He also has a temple at Rome with double doors, which they call the gates of war; for the temple always stands open in time of war, but is closed when peace has come.”

Macrobius describes them as two different structures as he recounts a battle between the Romans and the Sabines in his work, Saturnalia, IX.XVIII, while also recounting why this specific gate remained open during times of war:

“For this reason, the Romans who were guarding the entrance fled in terror: when the Sabines were about to burst through the open gate, it is said that a great force broke out from the house of Janus through this gate, with torrential waves, and many bands of traitors perished, either burnt by the boiling water or swallowed up by the swift torrent. In this matter, it was agreed that in time of war, as if to the aid of the city, surely the gods, the gates should be unlocked.”

In the book, Janus in Roman life and cult – a study in Roman religions (1918), author Bessie Burchett discusses the possibility that the Porta Ianualis was just an arch and no temple was present. Page XXXVII:

“The true representation of Janus was no statue or image of any kind: it was the arch in the Forum called Ianus Geminus, the gates of which were opened in time of war and closed in times of peace. This was the real Janus, the symbolical entranceway, the locus of the cult of the doorway of the state, just as Vesta, in her little round temple, was the symbolical hearth of the city. The arch was the god himself, and it was nearly always called “Janus,” not “temple of Janus” or “arch of Janus.” The gates were the “gates of Janus,” not the “gates of the arch of Janus.” The arch, at some time, contained a statue but Janus was not he image, or any spiritualization of it. The god was the doorway itself, and seldom was this thing called anything but “Janus.”

This is quite a creative and well-thought-out theory and makes some sense, particularly if you read further into the text. The author compares religion with the king in Rome and the father and the family. She then ties it together and explains how she came to the conclusion that the Porta Ianualis was nothing more than an arch.

However, Procopius describes the temple and the gates differently in his book, The Gothic Wars, Book I, XXV.XIX. He also explains the location of the temple:

“And he has his temple in that part of the forum in front of the senate-house which lies a little above the “Tria Fata”; for thus the Romans are accustomed to call the Moirai. And the temple is entirely of bronze and was erected in the form of a square, but it is only large enough to cover the statue of Janus. Now, this statue is of bronze and not less than five cubits high; in all other respects, it resembles a man, but its head has two faces, one of which is turned toward the east and the other toward the west. And there are brazen doors fronting each face, which the Romans in olden times were accustomed to close in times of peace and prosperity, but when they had war, they opened them.”

One issue I have with Procopius’ description is that he notes that the temple was made entirely of bronze.

His description was contemporary (he was in Rome as the legal advisor to General Belisarius), which poses the question: how does a temple made entirely of bronze survive the multiple sacks of Rome during the previous 130 years (three during that period)? Those that sack the city strip it of its most valuable objects and materials. This would have been a valuable structure to loot.

It is also somewhat surprising that an empire that was poor and needed to fund its armies would not repurpose this structure or strip it of its bronze, particularly since the empire was now predominantly Christian and the temple and gates were from the Pagan period.

Porta Stercoraria

We have little information on the Porta Stercoraria. It was doubtful that it was a gate to the city; it was more likely a gate used for more mundane purposes.

While this gate’s exact location is unknown, it was said to be located along the Clivus Capitolinus next to the Capitoline Hill.

According to author Lawrence Richardson in his book, A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (1992), page CCCIX:

“an alleyway on the Capitoline about midway on the ascent of the Clivus Capitolinus to which the refuse from the Temple of Vesta was carried and deposited on June 15.”

This could be seen as an annual ceremonial procession (of which there is no detail) or as simple housekeeping duties.

Porta Praetoriana

The Porta Praetoriana was one of the gates of the Castra Praetoria (the camp of the Praetorian Guard). It appears to be the only gate of the old Castra Praetoria that has survived antiquity after being bricked up and incorporated into the Aurelian Walls. It can found on the north-western side of the old Castra Praetoria.

By Gustavo La Pizza CC BY-SA 4.0

Porta Principalis Dextera

The Porta Principalis Dextera was one of the gates of the Castra Praetoria (the camp of the Praetorian Guard). It was either destroyed under Emperor Constantine when he abolished the guard or bricked up and incorporated into the Aurelian Walls.

Porta Decumana

The Porta Decumana was one of the gates of the Castra Praetoria (the camp of the Praetorian Guard). It was either destroyed under Emperor Constantine when he abolished the guard or bricked up and incorporated into the Aurelian Walls.

Porta Principalis Sinistra

The Porta Principalis Sinistra was one of the gates of the Castra Praetoria (the camp of the Praetorian Guard). It was either destroyed under Emperor Constantine when he abolished the guard or bricked up and incorporated into the Aurelian Walls.

Porta Ratumenna (Ratumena)

We do not have much information on the Porta Ratumenna. According to ancient sources, it was situated on or near the Capitoline Hill and dates from the Regal period or the early Republic.

According to legend, a charioteer was thrown from his chariot near the gate and killed, which is how it got its name. In the book Parallel Lives – The Life of Publicola, XIII.III, Plutarch explains the calamity:

“But a few days afterwards there were chariot races at Veii. Here, the usual exciting spectacles were witnessed, but when the charioteer, with his garland on his head, was quietly driving his victorious chariot out of the racecourse, his horses took a sudden fright, upon no apparent occasion, but either by some divine ordering or by merest chance, and dashed off at the top of their speed towards Rome, charioteer and all. It was of no use for him to rein them in or try to calm them with his voice; he was whirled helplessly along until they reached the Capitol and threw him out there at the gate now called Ratumena.”

There is conjecture whether the gate was located between the Capitoline and Quirinal Hills or on the Capitoline Hill itself, near the temple of Jupiter.

Porta Catularia

Details regarding the Porta Catularia are vague, with only limited references from ancient sources. As Lawrence Richardson notes in his book, A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (1992), page CCCI:

“Festus tells us that this gate got its name from the fact that not far from it, red dogs were sacrificed to appease the fury of the dog star and to ensure proper ripening of the grain.”

Ovid claims the gate was used during a religious procession.

It may have been a small door rather than a gate, and it would not have been a gate of great importance.

Porta Argiletana

Not much is known about the Porta Argiletana, mainly because it is found only in one historical source. Even then, the details are rather lacking.

Servius the Grammarian notes in his Commentary on Virgil’s Aeneid, Book VIII, CCCXLV:

“Others say that it is called the Argiletana gate because Cassius Argillus either built it or rebuilt it or because Cassius Argillus was killed there in the first Punic war because of his turbulent and seditious nature.”

It may have been an entry to the Argiletum, a street between the Subura and the Forum, near the Curia and Basilica Aemelia.

Porta Piacularis

The Porta Piacularis is not a gate on which we have a lot of information, with only one ancient source mentioning the existence of such a gate. As described by Lawrence Richardson in his book, A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (1992), page CCCVI:

“Known only from Festus (235L) and said to be so named because of a piacula performed there, which is less than helpful because piacula must have been performed at every gate, at least every gate of any importance.”

Just a note: piacula means sacrifices.

Porta Pompae (Circensis)

The Porta Pompae was located at the Circus Maximus. More precisely, it was located in the middle of the carceres end of the Circus (the Tiber River end), where the circus procession entered the arena.

It was said to be a gate that was always open, which raises the question of whether it was a gate that was always open or just an arch, vaulted or otherwise.

Porta Libitinensis

The Porta Libitinensis is a gate in Rome that served a specific purpose. It was the gate that was used to carry dead bodies from the arena.

This appears to be a gate at all the arenas, as it is attested to be located at the Circus Maximus and the Colosseum. It was named after the god of funerals, Libitina.

When noting a specific time during the reign of Emperor Commodus, one in which there were bad omens and the city fell under darkness, the Historia Augusta – The Life of Commodus, XVII.VI mentions the gate:

“He was himself responsible for no inconsiderable an omen relating to himself; for after he had plunged his hand into the wound of a slain gladiator, he wiped it on his own head, and again, contrary to custom, he ordered the spectators to attend his gladiatorial shows clad not in togas but in cloaks, a practice usual at funerals, while he himself presided in the vestments of a mourner. Twice, moreover, his helmet was borne through the Gate of Libitina.”

Not much is known about the Porta Navalis except that it was located in the vicinity of the Navalia (docks), which was located somewhere along the Tiber (possibly in the general vicinity of Tiber Island or a little further south).

Porta Fenestella

The Porta Fenestella appears to have been nothing more than a doorway rather than a city gate of any importance during the regal period.

It was said to have been located near the Via Sacra, possibly near the temple of Fortuna. Legend has it that King Servius Tullius was visited by Fortuna through this gate (which was almost certainly a door or window).

Plutarch poses a question regarding this. While not giving an answer in his work, Roman Questions, IV.XXXVI, he does allude to the possibility of the size of the gate:

“Why do they call one of the gates the Window, for this is what fenestra means, and why is the so‑called Chamber of Fortune beside it?

Is it because King Servius, the luckiest of mortals, was reputed to have conversed with Fortune, who visited him through a window?

Or is this but a fable, and is the true reason that when King Tarquinius Priscus died, his wife Tanaquil, a sensible and queenly woman, put her head out of a window and, addressing the citizens, persuaded them to appoint Servius king, and thus the place came to have this name?”

Sources:

Dionysius of Halicarnassus – Roman Antiquities (Thayer)

Virgil – Aeneid (Perseus Digital Library)

Solinus – On the Wonders of the World (the Latin Library)

Livy – The History of Rome (Perseus Digital Library)

Strabo – Geography (Thayer)

Plutarch – The Parallel Lives (Thayer)

Tacitus – Annals (Thayer)

Rodolfo Lanciani – Pagan and Christian Rome (Thayer)

Valerius Maximus – Factorum et Dictorum Memorabilum Libri Novem (the Latin Library)

Procopius – The Gothic Wars (Thayer)

British School at Rome – Papers of the British School at Rome

Ammianus Marcellinus – The Roman History (Thayer)

Lawrence Richardson – A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome

Historia Augusta (Thayer)

Macrobius – Saturnalia (Thayer)

Bessie Burchett – Janus in Roman life and cult – a study in Roman religions

Servius the Grammarian – Commentary on Virgil’s Aeneid (ToposText)

Plutarch – Roman Questions (Thayer)