Ancient civilizations were built on strong leadership, military prowess, decisive action, and political smarts. Emperors needed a good dose of all of the above to be successful. Over the 500 years of the Roman Empire, many have worn the imperial robe. So, without further ado, here is a list of six of the best Roman emperors (not in any order).

Augustus

(Reign 16th January 27 BC – 19th August AD 14)

Well, it’s hard to go past the very first emperor. Without the first, no subsequent ones exist, so number one is always a trailblazer. Yes, the groundwork for his trailblazing was for the main part set up by Julius Caesar. However, Octavian still had work to do before becoming Augustus.

While Octavian was not the most remarkable military general, he was quite cunning in the political sphere and a brilliant strategist. On many occasions, he formed alliances (albeit brief at times) with enemies to serve a political purpose or to advance his own cause.

His alliance with Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony) and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus brought about the second triumvirate, consolidating power between the three men. This allowed all three men to go after political opponents, including Julius Caesar’s assassins. All three were granted control over different sections of Roman-controlled land.

Events over the following few years led to Lepidus’ banishing from the triumvirate, with Octavian seizing his territories. A further falling out between Octavian and Antony dissolved their alliance, with Antony based in Egypt with Cleopatra.

This culminated in the battle of Actium between Octavian’s forces, commanded by Marcus Agrippa and Gaius Sosius, and the forces of Mark Antony. Antony was defeated and returned to Egypt, where he subsequently committed suicide, with Cleopatra doing likewise a short time later.

After these events, Octavian spent the next few years consolidating power through political maneuvering and gained the title of Augustus on 16th January 27 BC.

Augustus died on 19th August AD 14, but not before adding modern-day northern Spain and Portugal, Judea, and parts of modern-day Turkey, as well as modern-day Switzerland, Slovenia, Albania, Hungary, Austria, Bavaria, Croatia, and Serbia as Roman territories.

A critical psychological and symbolic victory for Augustus and the Romans was that the empire regained the lost Eagle standards that were given up by Marcus Crassus in the disastrous battle at Carrhae, thanks to some shrewd negotiating by Augustus’ stepson and future emperor, Tiberius.

He also formally integrated the first firefighters and police in Rome – the Vigiles (Vigiles Urbani) and Urban Cohorts (Cohortes Urbanae).

His time as emperor brought about the Pax Romana (Roman peace), a period of stability for the empire that lasted around two centuries. He also instituted a courier system throughout the empire, enabling swifter communication anywhere within Roman lands.

He also changed the role of the Praetorian Guard. Once only deployed around military camps for generals, it now served as the emperor’s permanent bodyguard.

Augustus unified the entire Italian peninsula into what basically became Italia, or Roman Italy, in 7 BC.

He built many temples and other public buildings, including forums, baths, and theaters. He also improved the road system and Rome’s water supply. His tax reforms enabled a steadier stream of income into the coffers of the Roman state from its provinces.

Augustus left a legacy that was not matched by any emperor, and his reforms led to the empire’s longevity. According to Cassius Dio in his book, Roman History, Book LVI, XXX, Augustus quipped on his deathbed:

“I found Rome of clay; I leave it to you of marble.”

Vespasian

(1st July AD 69 – 23rd June AD 79)

After beginning his service in the Roman military under Rome’s second emperor, Tiberius, Vespasian (Titus Flavius Vespasianus) gained minor political office under Rome’s third emperor, Caligula, before taking part in the invasion of Britannia under Rome’s fourth emperor, Claudius. He was involved in the Judean war under Rome’s fifth emperor, Nero. Then, he endured the short reigns of Galba (seven months), Otho (three months), and Vitellius (eight months). After this period of instability, Vespasian became Rome’s ninth emperor. This marked the start of the 27-year Flavian dynasty.

His first actions as emperor were to reform the tax system and introduce new taxes. This was done so the imperial treasury could be filled after years of out-of-control spending by Nero. He also put down a revolt in Gaul and finally ended the revolt in Judea.

While he did not expand the empire, his reign came at a time of significant instability, following the reign of the crazed Nero and the short reigns of Galba, Otho, and Vitellius. A period of stability was needed, with his reign lasting just shy of ten years.

By Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0

Although his reign was marred by propaganda and the silencing of opponents, his ultimate success was building the Colosseum. The Colosseum was built using the spoils of war in Judea. It was seen as an essential public space for Roman society, from the imperial family all the way down to the plebeians.

Central to this importance was that it was built on top of land Nero reclaimed after the fire of AD 64 and used for his own private lake, turning a private space of a disliked emperor into a space to be enjoyed by all, played well politically for Vespasian.

The Colosseum has become synonymous with ancient Rome. It was a place where Romans from all classes of society could gather and enjoy the fruits of Roman conquest and power. Unfortunately, Vespasian never lived long enough to see the Colosseum used, as he passed away around six months before it opened.

Overall, he brought some stability to the empire at a time when it was much needed. He also constructed one of the ultimate symbols of the Roman civilization, which was enjoyed by everyone.

Trajan

(28th January AD 98 – 11th August AD 117)

It was under the emperor Trajan that the Roman Empire reached its largest geographical extent. His reign netted the Roman Empire the territories of Dacia (modern Romania), Nabataea (located in the southern Levant, the Sinai Peninsula, northwestern Arabian Peninsula, with its capital of Petra), Armenia, Mesopotamia, and Assyria. The Roman Empire now extended from the north of England to Mesopotamia.

Trajan was also a prolific builder. Thanks to the help of renowned architect Apollodorus of Damascus, Trajan constructed many buildings within Rome, chief among them being Trajan’s Forum (Forum Traiani). This Forum contained a few buildings, including the Forum Square, Basilica Ulpia, Temple of Trajan, a bronze equestrian statue of Trajan, Latin and Greek Libraries, Trajan’s Market, and Trajan’s Column.

He constructed many triumphal arches throughout the empire, roads such as the Via Traiana, and extended the Via Appia. He also built the Via Traiana Nova, a road from Damascus to Aila (in modern-day Jordan). He also built several palatial villas.

He was also responsible for increasing the size of the Circus Maximus by a few thousand seats.

Trajan was also responsible for returning some of the private property that was seized under Emperor Domitian, making him a more popular figure.

By Marco Almbauer – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Trajan continued a trend of previous emperors of devaluing the Roman currency, reducing the silver content of minted coins. This would have disastrous ramifications in a couple of hundred years as future emperors continued the trend, but it did allow the emperor to help orphaned and poor children by providing money, food, and education.

He could probably afford to do it, as he was still enjoying the spoils of war and could bring more money into the empire. However, as no further territories were gained after his reign, the process of devaluing the currency by future emperors became more catastrophic.

In his book, Breviarium Historiae Romanae, fourth century AD author Eutropius writes regarding Trajan in Book VIII, V:

” So much respect has been paid to his memory that, even to our own times, they shout in acclamations to the emperors, “More fortunate than Augustus, better than Trajan!” So much has the fame of his goodness prevailed, that it affords ground for most noble illustration in the hands either of such as flatter, or of such as praise with sincerity.”

Overall, Trajan added a lot to the Roman Empire. The currency devaluation was a black mark on his reign, but the consequences weren’t known at the time, and it was a continuation of something that previous emperors had undertaken.

Marcus Aurelius

(7th March 161 – 17th March 180)

Marcus Aurelius was a stoic philosopher and the last emperor to reign during the Pax Romana (Roman peace).

With his co-emperor, Lucius Verus, leading the military campaign, Marcus pushed back a Parthian invasion of Armenia and Mesopotamia in the mid-160s AD. The Parthians had been a problem for the Romans again since the reign of their predecessor, Antoninus Pius.

Shortly after this military victory, they turned their attention to the Danube border region, with Germanic tribes beginning to attack the now poorly defended northern frontier. AD 166 saw the Marcomanni, Lombards, Sarmatians, and Costoboci all cross the Danube into Roman territory. Marcus eventually pushed back these tribes, but times were changing – barbarian tribes seemed more likely to want to cross the border into Roman territory now than they had previously.

Throughout his time as emperor, he was a prolific writer. One such body of work is what we now know as Meditations (we don’t actually know the name that he gave this body of writing). It is his innermost thoughts while it acts as a guide to self-improvement. It is still revered today as a masterpiece in stoic philosophy.

Overall, his battles against the Parthians and his extraordinary 14-year war against the Germanic tribes in the Marcomannic Wars kept the enemies at bay. He did, however, further devalue the Roman currency. He then reversed that almost entirely before devaluing again. It became an ongoing issue for Rome, mainly because no new territory was being conquered. His other error was naming his son, Commodus, his heir. Commodus ended up being one of Rome’s worst emperors, which was the precursor to the crisis of the third century.

Lastly, the enduring legacy of his writings is a huge plus, with many people today still finding value in the writings of a Roman emperor more than 18 centuries ago.

Aurelian

(AD 270 – 275)

Although he only reigned for five years, his reign was packed full of action. After serving competently under emperors Gallienus and Claudius Gothicus, Aurelian became emperor during a tumultuous time for the empire.

The crisis of the third century was a disaster for the empire, which had seen many revolts and claimants to the throne. By the time Aurelian came to power, Gaul and Britannia had seceded and became the Gallic Empire, while the easternmost provinces, including Egypt and Syria, seceded and became the Palmyrene Empire.

By Giovanni Dall’Orto. – Own work, Attribution, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15683121

He began his reign with battles against various barbarian tribes (Sarmatians, Vandals, and Juthungi) in northern Italy, defeating them all and pushing them back beyond the empire’s borders. After a visit to Pannonia, Aurelian returned to Italy to drive out the invading Alamanni, described by Zosimus in his book, New History, Book I, XLIV:

“The Emperor, hearing that the Alemanni and the neighboring nations intended to over-run Italy, was with just reason more concerned for Rome and the adjacent places than for the more remote. Having therefore ordered a sufficient force to remain for the defense of Pannonia, he marched towards Italy, and on his route, on the borders of that country, near the Ister, slew many thousands of the Barbarians in one battle.”

For these victories, he was bestowed the honorific title of Germanicus Maximus.

Shortly after this time, he returned to Rome and began the construction of the walls that now bear his name – the Aurelian Walls. Rome was seen as not properly fortified, while the city had grown beyond the walls that had been previously built. The walls were thicker and much taller than any previous city fortification.

He left Italy and headed to the Danube border in the Balkans, where he trounced the Goths and expelled them from Roman territories. He was then given the title of Gothicus Maximus. During this time, he also withdrew from Dacia, figuring it was too difficult for the empire to maintain amid constant invasions. Consolidating his empire south of the Danube was his priority, as it was easier for the empire to defend.

By Blank map of South Europe and North Africa.svg: Blank map of South Europe and North Africa.svgRomanworld271AD.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0

His next mission lay eastward and the Palmyrene Empire. He recaptured the lands in Asia Minor with relative ease and, within a year, had recaptured the lands of the Palmyrene Empire, which had included Asia Minor, Egypt, Palestine, and Syria. This victory also secured the vital grain shipment from Egypt to Rome, which was critical to sustaining the eternal city. From these victories, he received the titles of Parthicus Maximus and Restitutor Orientis (Restorer of the East).

By the fourth year of his reign (AD 274), Aurelian turned his attention to the last of the rebellious provinces, Gaul and Britannia, which was known at this time as the Gallic Empire. This was regained mainly without bloodshed, with Aurelian’s diplomatic skills coming to the fore.

Upon reuniting the empire, in the space of four years, Aurelian returned to Rome. Here, he received his greatest title – Restitutor Orbis (Restorer of the World).

Apart from military victories, he also reformed parts of the Roman state. This included arresting corrupt officials and mint workers, religious reforms (allowing people to worship one God in Sol Invictus), coinage reform to tackle the constant devaluation of the Roman currency and food distribution reforms that added the distribution of olive oil, salt and pork to the usual bread dole.

He also restored many public buildings. The city of Orleans in France was named after Aurelian after he had rebuilt the original town of Cenabum and called it Aurelianum.

Overall, given we are talking about the crisis of the third century, where emperors were regularly assassinated (Aurelian fell victim to this as well), and the armies of Rome had started to become weak, his feats are quite extraordinary and puts him up there with the greatest Roman emperors the empire has ever seen. What could have been had his reign not been cut short by his own soldiers?

Majorian

(28th December AD 457 – 2nd August AD 461)

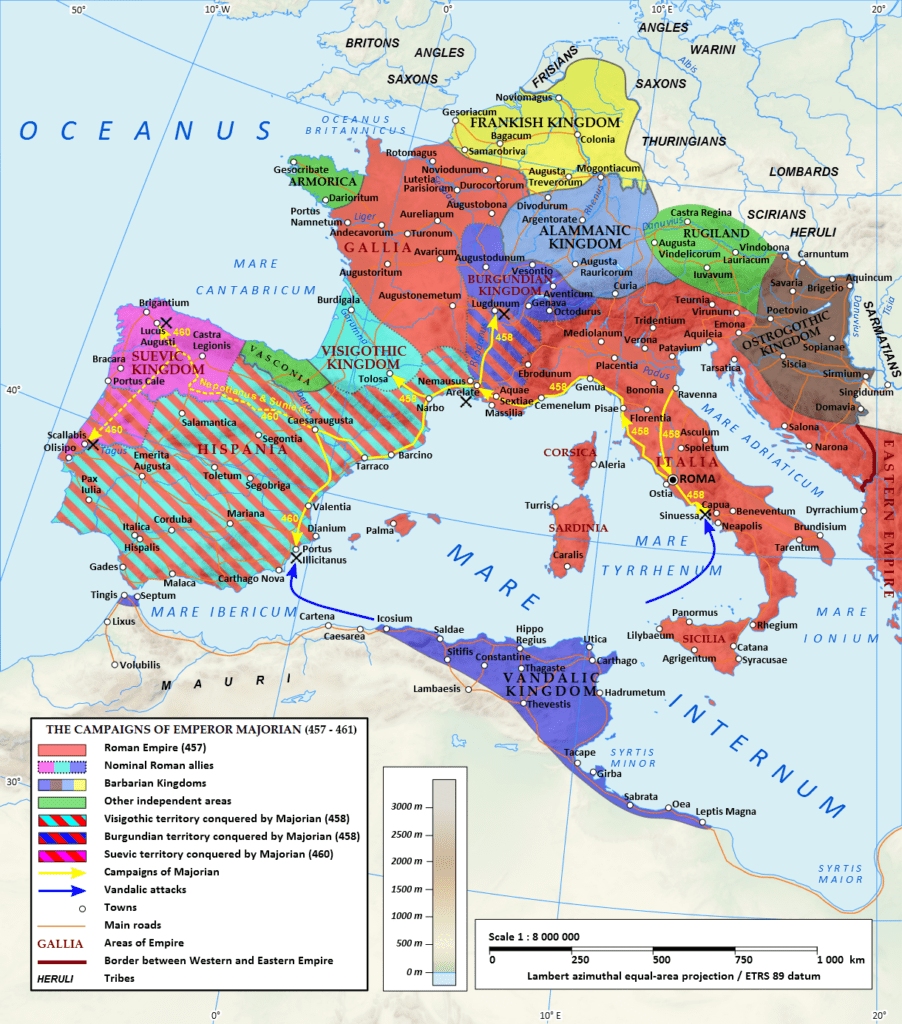

Like Aurelian, Majorian’s reign was short-lived but quite incredible. He rose to become emperor at a time when the Western Roman Empire was little more than the Italian peninsula, Corsica, Sardinia, parts of modern-day Slovenia, and parts of Gaul.

His first job was to repel the Vandals who landed in southern Italy. He soundly defeated them, which was quite the contrast to two years earlier when the Vandals violently sacked Rome.

By icollector.com – CC BY-SA 3.0

Majorian then turned his attention to reconquering Gaul, entering the territory in AD 458 with his mostly barbarian army.

It must be noted that Roman armies of this period mainly consisted of barbarian foederati (troops supplied by client kingdoms to the Romans through treaties in exchange for money), as it had become almost impossible to recruit Roman citizens. This was because soldiers were paid much less (mainly due to currency devaluation). At the same time, the quality of Roman forces led to defeat after defeat on the battlefield. The declining population in the West also affected the pool of troops that could be recruited. Finally, the loss of wealthy provinces meant the Roman state did not have enough money to support an army that was appropriately trained and equipped in sufficient numbers.

Upon entering Gaul, Majorian led his army to victories over the Visigoths, who were forced to hand over land in Gaul and Hispania. They also had to become a client of Rome, supplying the Romans with troops while being able to keep a small part of the land they had previously occupied.

Bolstered by Visigothic foederati soldiers, Majorian led his army into battle against the Burgundians who occupied eastern Gaul. Success against the Burgundians meant they suffered the same fate as the Visigoths – they gave up land and became a client state of Rome, supplying the Romans with foederati soldiers.

The conquest of Hispania was next on the list, with the Romans heading south in AD 459. While traveling to Hispania, he sent an army to Sicily to recapture it from the Vandals, which was ultimately successful. By 460, most of Hispania had been reconquered.

It was while in Hispania that preparations were being made to sail to Africa and to re-take the provinces that were lost to the Vandals. As fate would have it, though, the fleet that the Romans had assembled (at a significant cost) was destroyed in the port of Portus Illicitanus (near modern Elche). Rumor has it that he was betrayed either by the local population or someone who had knowledge of the plans to sail to Africa. This disastrous turn of events forced Majorian to abandon his plans of reconquering Africa.

By Tataryn – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

In AD 461, on the way back to Italy, he was confronted by long-time friend and Magister Militum, Ricimer, where he was arrested and executed a few days later.

Away from the battlefield, Majorian enacted several laws aimed at preserving old imperial buildings, which were at the time subject to plundering. He actively sought to rebuild and maintain these structures; such was his belief in the Roman state.

He enacted laws to try and boost the ailing population growth, forbidding women of child-bearing age from taking religious vows that stopped them from having children.

He also reformed tax collection procedures to stamp out rampant corruption. He enacted other policies to reform the Roman state. He was, as history would now see, Rome’s last great hope before the ‘fall’ of the Empire in AD 476.

Overall, what Majorian achieved, given the turmoil in Europe at the time and the lack of everything an empire needed for conquest, was remarkable. He was able to expand the Roman borders once again, gaining vital funds for the ailing empire. The inability to take Africa was quite detrimental to Rome’s chances for survival, but this cannot be blamed on Majorian. Had he not been killed after only four years in charge, the fate of Rome could have been set on a very different course.

As the historian Edward Gibbon wrote about Majorian in his classic piece of historical literature, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Volume III, Chapter XXXVI:

“Majorian……. presents the welcome discovery of a great and heroic character, such as sometimes arise in a degenerate age, to vindicate the honor of the human species. “

The Romans had a lot of emperors over the years – some great and some diabolical. These are some of the best.

Sources:

Roman History – Cassius Dio (Thayer)

Breviarium Historiae Romanae – Eutropius (Tertullian.org)

New History – Zosimus (Tertullian.org)